Swipe Fatigue and the Friendship Gap: Why Dating Apps Don’t Fix Men’s Loneliness

Dating apps promise connection.

Before going further, it is worth being transparent about my own position in this discussion. I have never used a dating app to find romance. I was married and raising children long before these platforms became a dominant way people met. My own relationship formation followed a more traditional path, one that came with its own constraints, blind spots, and challenges. With a few swipes, users can access more potential partners than at any other point in human history. Yet for many men, especially young adult men, this abundance has coincided with persistent, and in some cases worsening, loneliness. The gap between promise and outcome raises a basic question: if access to people is no longer the problem, why does connection still feel so scarce?

This essay wasn’t designed to dump on dating apps, but to highlight how they ineffectively reduce men’s loneliness and can be structurally misaligned with the kinds of social environments that produce durable connections. The conclusions presented are not drawn from personal nostalgia for an earlier era of dating, but from a growing body of empirical research that raises serious questions about whether the benefits of these platforms outweigh their costs for many users. Drawing on research from social psychology, communication, and public health, I describe dating apps within a broader framework of friendship markets: the social contexts that make relationship formation possible in the first place.

Friendship Markets and Why They Matter

Friendship markets are not metaphors for romance or sexual exchange. They are environments where many people are simultaneously open to forming new relationships, where interaction is repeated rather than transactional, and where vulnerability is socially permitted. Empirical work on adult friendship formation shows that proximity, repeated interaction, and shared transitions are critical drivers of relational development (McCabe, 2016). When these conditions weaken-as they often do after school, early career stages, or major life transitions-friendship formation declines, even when social motivation remains high.

Men are differentially affected by the collapse of these markets. Survey research consistently shows that men report fewer close friends than women and are more likely to experience chronic loneliness (Apostolou et al., 2024; Thomas et al., 2022). These patterns are not well explained by individual deficits alone. Instead, they reflect the erosion of institutions that historically generated friendship markets for men, such as stable workplaces, civic organizations, and activity-based groups.

Dating Apps as Closed Markets

My distance from dating apps also shapes how I read this evidence. Because I did not experience these platforms firsthand, I approach them less as cultural common sense and more as social systems whose effects have to be demonstrated rather than assumed. In that sense, the findings summarized below were not obvious to me in advance; they emerged from the research.

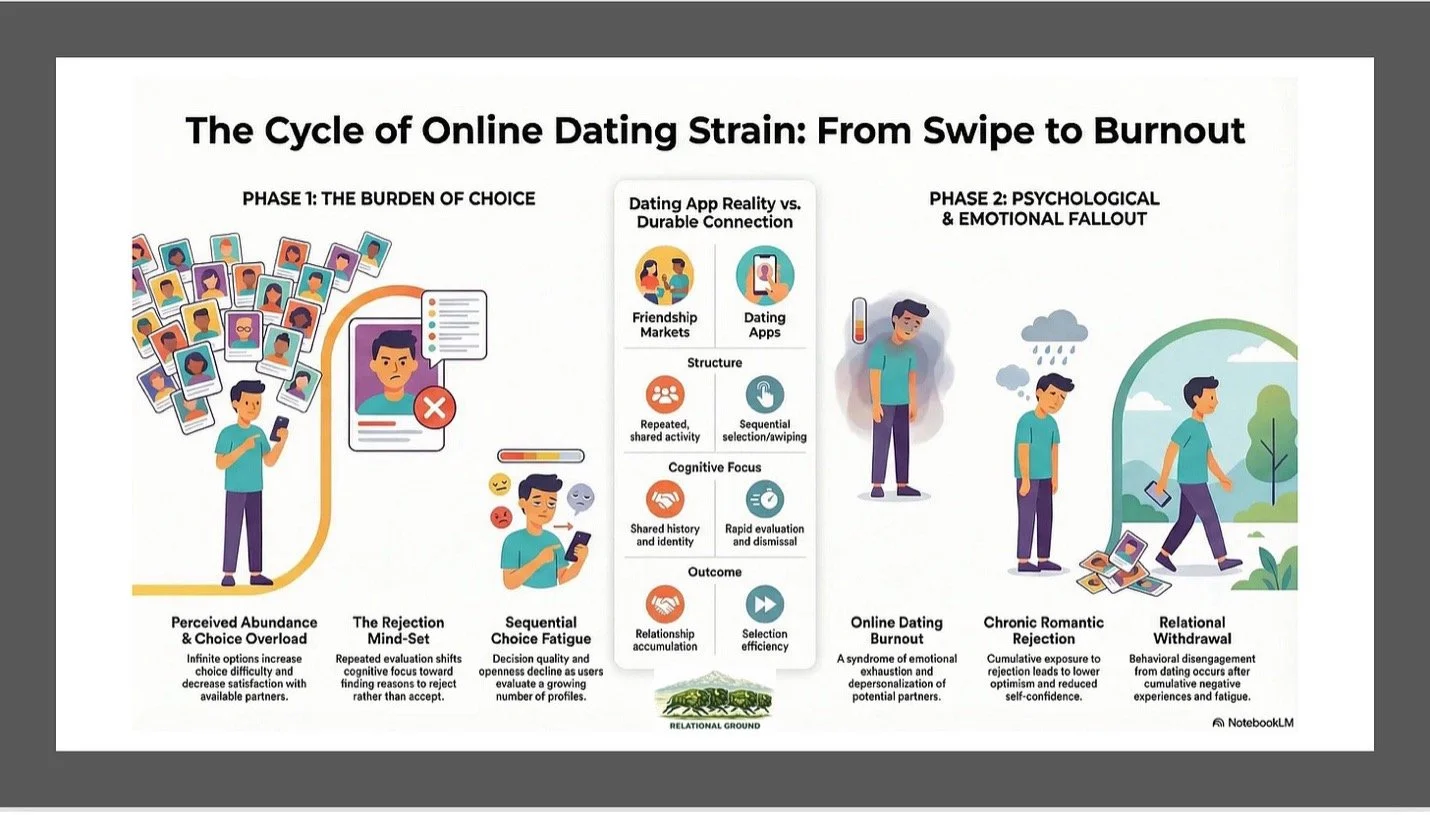

Dating apps are often treated as substitutes for these lost markets. But empirically, they function very differently. Rather than creating environments of shared availability, dating apps are designed around sequential selection: users evaluate profiles one at a time, making rapid accept-or-reject decisions. Experimental research demonstrates that this structure reliably produces choice overload and declining openness over time.

Pronk and Denissen (2019) showed that as users evaluate increasing numbers of profiles, they develop what the authors call a rejection mindset: acceptance rates decline even when the objective quality of profiles remains constant. This effect was observed across multiple laboratory experiments and is not attributable to fatigue alone. Instead, repeated evaluation shifts users’ cognitive orientation toward finding reasons to reject rather than accept.

Field and laboratory studies replicate related dynamics. Thomas et al. (2022) found that exposure to larger assortments of potential partners increased fear of being single and reduced satisfaction, even as perceived opportunities increased. Another experimental study, Thomas et al. (2023), demonstrated that excessive swiping was associated with lower well-being, which was articulated through increased social comparison and compulsive use patterns.

Together, these findings suggest that dating apps function as closed markets for men and women: they offer access without the relational scaffolding required for connection to accumulate.

Swipe Fatigue and Burnout

Beyond choice overload, sustained dating app use is associated with emotional exhaustion. Balassanian (2025) conceptualizes online dating burnout as a syndrome closely resembling occupational burnout, characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization of potential partners, and withdrawal from dating activity. In her dissertation study, higher burnout scores were associated with greater app use intensity and stronger mismatches between users’ relational goals and platform design.

Notably, men in this sample reported significantly higher levels of burnout than women, even after controlling for use frequency. This finding aligns with evidence that men experience lower match rates and more unreciprocated initiation on dating apps. This in-app experience increases their exposure to rejection and depletion¹ (Pronk & Denissen, 2019; Thomas et al., 2023).

Rejection as a Cumulative Exposure

Rejection is not inherently harmful. However, clinical and survey-based research suggests that chronic romantic rejection has measurable mental health consequences. Using nationally representative survey data, Ly (2024) found that individuals who perceived romantic rejection as frequent and enduring reported lower optimism, reduced self-confidence, and greater avoidance of future relational efforts.

Importantly, these outcomes were not driven by single experiences but by cumulative exposure. This framing aligns with public health models of risk, where repeated low-level stressors can produce downstream harm over time. Dating apps, by design, increase exposure frequency while minimizing opportunities for relational repair or contextual explanation (Pronk & Denissen, 2019; Thomas et al., 2023; Medina-Bravo et al., 2023; Ly, 2024).

Why Dating Apps Don’t Build Friendship

Sociological research on friendship formation underscores that friendships are not merely sources of companionship but core sites of identity construction. In a qualitative study of emerging adults, Anthony and McCabe (2015) show that people actively define who they are through what they call friendship talk: the narratives individuals use to describe, evaluate, and contextualize their friendships. These narratives rely on repeated interaction, shared history, and the ability to make sense of oneself through others over time. Friendship formation, in this view, is not a single decision but an ongoing relational process tied to identity work.

Men’s loneliness is not only about romance. Evidence shows that men with fewer close friendships are more likely to feel dissatisfied and struggle to form lasting romantic relationships, even when dating options exist (Apostolou et al., 2024; Thomas et al., 2022). Yet dating apps are often used to address unmet needs for companionship, affirmation, and belonging.

Empirically, this is a category error. Dating apps optimize selection efficiency, not relationship accumulation. They provide no mechanism for low-stakes repetition, shared activity, or gradual escalation of intimacy-all of which are core components of friendship formation. Qualitative research on dating app experiences underscores this limitation: users describe interactions as fast, evaluative, and emotionally thin, even when frequent (Medina-Bravo et al., 2023).

Dating Apps as a Public Health Issue

From a public health perspective, the question is not whether dating apps harm everyone, but whether they function as risk environments for certain populations. Systematic reviews of problematic dating app use consistently link intensive use to distress, anxiety, and reduced well-being, while noting the predominance of cross-sectional designs (Thomas et al., 2025).

For men already navigating thin friendship markets, dating apps may exacerbate isolation by substituting selection for connection. Over time, repeated rejection, comparison, and burnout can encourage withdrawal rather than engagement, precisely the opposite of what loneliness interventions require.

Toward Better Friendship Markets

My own experience of forming relationships before the rise of dating apps may push me toward approaches that emphasize shared activity, institutional support, and gradual familiarity. But what is striking is that these intuitions are now being echoed by empirical research, not contradicted by it.

The empirical literature suggests that reducing men’s loneliness requires rebuilding IRL experiences like friendship markets (see: Friendship Markets blog), not refining dating algorithms. Effective markets share three features: simultaneous openness to connection, repeated interaction over time, and shared purpose or transition. These conditions are consistently associated with friendship formation across the life course (McCabe, 2016).

Dating apps cannot supply these features on their own. Community-based groups, activity-centered spaces, and cohort-based programs are better positioned to do so. Treating men’s loneliness as a design and infrastructure problem, rather than a personal failure, opens new avenues for intervention.

Dating apps are not failing because men are broken. They are failing because they are being asked to solve a problem they were never designed to address. The evidence is clear: access without infrastructure does not produce connection. If we want to reduce men’s loneliness, we must invest in friendship markets that support repeated, reciprocal, and meaningful social ties.

*See list of relevant dating terms at the bottom of the blog.

¹ Depletion refers to the gradual erosion of cognitive, emotional, and motivational resources that occurs through repeated evaluative decisions and exposure to non-reciprocity. In the dating app literature, depletion is observed among both men and women and is reflected in declining openness to new partners, increased reliance on heuristics, emotional exhaustion, and reduced willingness to initiate or invest effort over time, although exposure patterns and downstream consequences may differ by gender (Pronk & Denissen, 2019; Thomas et al., 2023; Balassanian, 2025).

References

Apostolou, M., Shialos, M., & Georgiadou, P. (2024). Mate choice plurality, choice overload, and singlehood. Behavioral Sciences, 14(8), 703. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080703

Balassanian, N. (2025). Swiped out: Online dating burnout (Doctoral dissertation). Alliant International University.

Ly, J. (2024). Online dating rejection experiences and mental health outcomes (Doctoral dissertation). Azusa Pacific University.

McCabe, J. (2016). Connecting in college: How friendship networks matter for academic and social success. University of Chicago Press.

Medina-Bravo, P., Figueras-Maz, M., & Gómez-Puertas, L. (2023). Tinder un-choosing: The six stages of mate discarding in a patriarchal technology. Feminist Media Studies, 23(7), 3175-3191. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2022.2099928

Pronk, T. M., & Denissen, J. J. A. (2019). A rejection mind-set: Choice overload in online dating. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 11(3), 388-396. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550619866189

Thomas, M. F., Binder, A., Stevic, A., & Matthes, J. (2022). The agony of partner choice: Too many options, too little satisfaction. Computers in Human Behavior, 126, 106977. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106977

Thomas, M. F., Binder, A., Stevic, A., & Matthes, J. (2023). 99+ matches but a spark ain’t one: Adverse psychological effects of excessive swiping on dating apps. Telematics and Informatics, 78, 101949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2023.101949

Thomas, M. F., Stevic, A., Binder, A., & Matthes, J. (2025). Problematic online dating: A systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 27, e72850. https://doi.org/10.2196/72850

Key Terms, Author-Provided Definitions, and Sources

Rejection Mind-Set

“A rejection mind-set refers to a cognitive orientation that develops when people are repeatedly confronted with many potential partners, leading them to increasingly focus on reasons to reject rather than accept subsequent options. Over time, this mind-set results in systematically lower acceptance rates, even when objective partner quality does not decline.” - Pronk, T. M., & Denissen, J. J. A. (2019).

Choice Overload (in Online Dating)

“Choice overload occurs when an abundance of available options leads to poorer decisions, decreased satisfaction, and a greater likelihood of deferring or avoiding choice altogether, rather than improving outcomes.” - Pronk, T. M., & Denissen, J. J. A. (2019).

Sequential Choice Fatigue

“As users evaluate a growing number of profiles sequentially, their decision quality and openness to new partners decline, suggesting that repeated partner evaluations deplete motivational and cognitive resources.” - Thomas, M.F, et al., (2023).

Swipe Fatigue

“Swipe fatigue describes a state of emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and disengagement that emerges from prolonged interaction with dating apps, particularly when users’ relational goals are misaligned with the platform’s gamified design.” - Balassanian, N. (2025).

Online Dating Burnout

“Burnout in online dating mirrors occupational burnout and consists of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization of dating partners, and reduced feelings of accomplishment or efficacy in forming relationships.” Balassanian, N. (2025).

Choice Capacity

“Choice capacity refers to the number of options users can meaningfully process before additional options reduce engagement, satisfaction, or matching success. This capacity varies systematically across users and contexts.” Jung, et al., (2022).

Decision Fatigue

“Decision fatigue occurs when repeated decision-making leads individuals to rely more on heuristics, disengage from choices, or delegate decisions to external systems, resulting in lower satisfaction and reduced agency.” - Thomas, et al., (2025).

Locomotion Decision Mode

“Locomotion reflects a self-regulatory orientation focused on movement and progress, emphasizing speed and action over evaluation. In dating apps, this orientation manifests as rapid swiping with limited deliberation.” - Thomas et al. (2025).

Assessment Decision Mode

“Assessment reflects a self-regulatory orientation focused on comparison, evaluation, and correctness, which can become psychologically burdensome when the number of available options is large.” - Thomas et al. (2025).

Perceived Abundance of Alternatives

“Perceived abundance of alternatives refers to the subjective belief that one has many viable mating options, which can undermine commitment and increase dissatisfaction with available partners.” - Apostolou, M. (2024).

Mate Choice Plurality

“Mate choice plurality denotes the perception that multiple potential mates are simultaneously available, increasing choice difficulty and, in some cases, contributing to prolonged singlehood.” - Apostolou, M. (2024).

Fear of Being Single

“Fear of being single reflects concern about long-term romantic solitude and can paradoxically increase when individuals are exposed to large numbers of potential partners.” - Thomas, M.F. (2022).

Gamification (of Dating Apps)

“Gamification refers to the application of game-design elements such as swiping, rewards, and variable reinforcement schedules, which increase engagement but may reduce relational depth.” - McCarthy, C. (2022).

Partner Disposability

“Dating apps normalize the perception that potential partners are easily replaceable, encouraging rapid dismissal and reducing emotional investment in any single interaction.” - Medina-Bravo et al. (2023).

Mate Discarding

“Mate discarding is a multi-stage process through which users progressively eliminate potential partners, often with minimal interaction, facilitated by platform affordances.” - Medina-Bravo et al. (2023).

Chronic Romantic Rejection

“Chronic rejection is experienced when individuals perceive romantic rejection as frequent, enduring, and uncontrollable, rather than situational or episodic.” - Ly (2024)

Relational Withdrawal

“Relational withdrawal refers to behavioral disengagement from romantic pursuit following cumulative negative experiences such as rejection, fatigue, or emotional exhaustion.” - Ly (2024); Balassanian (2025).