The Collapse of Workplace Friendship

The Hidden Health Cost of Remote Work, Turnover, and Hustle Culture

My friend Jolles and I lived in the northern stretch of Durham, NC. We both like to bike. In the humid early mornings, he and I would barrel down Guess Rd. beside the cars on our 16-mile trek to work. Despite onsite showers, most days I wouldn’t really stop perspiring until 10:00 am. Beyond the workout, the rides provided opportunities to talk about sports, movies, family stuff, and sometimes make plans for the weekend.

Even though we didn't work on the same projects, we'd often drop in on one-another, eat together or refer to something stupid that happened on the ride in. These were small, unplanned moments that made the workday feel less isolating and more human. Jolles left the organization and moved to California about a year before I moved up to the DMV. When he left, it wasn’t just a colleague I lost, it was one of the few built-in rituals that kept friendship within my daily work calendar.

For many men, work is an important place where friendship can be facilitated by common experience. Not because work was designed to foster intimacy, but because it quietly provided the conditions that make connection possible: repeated interaction, shared purpose, and low-stakes proximity. You showed up. Other people showed up, and relationships accumulated in the background.

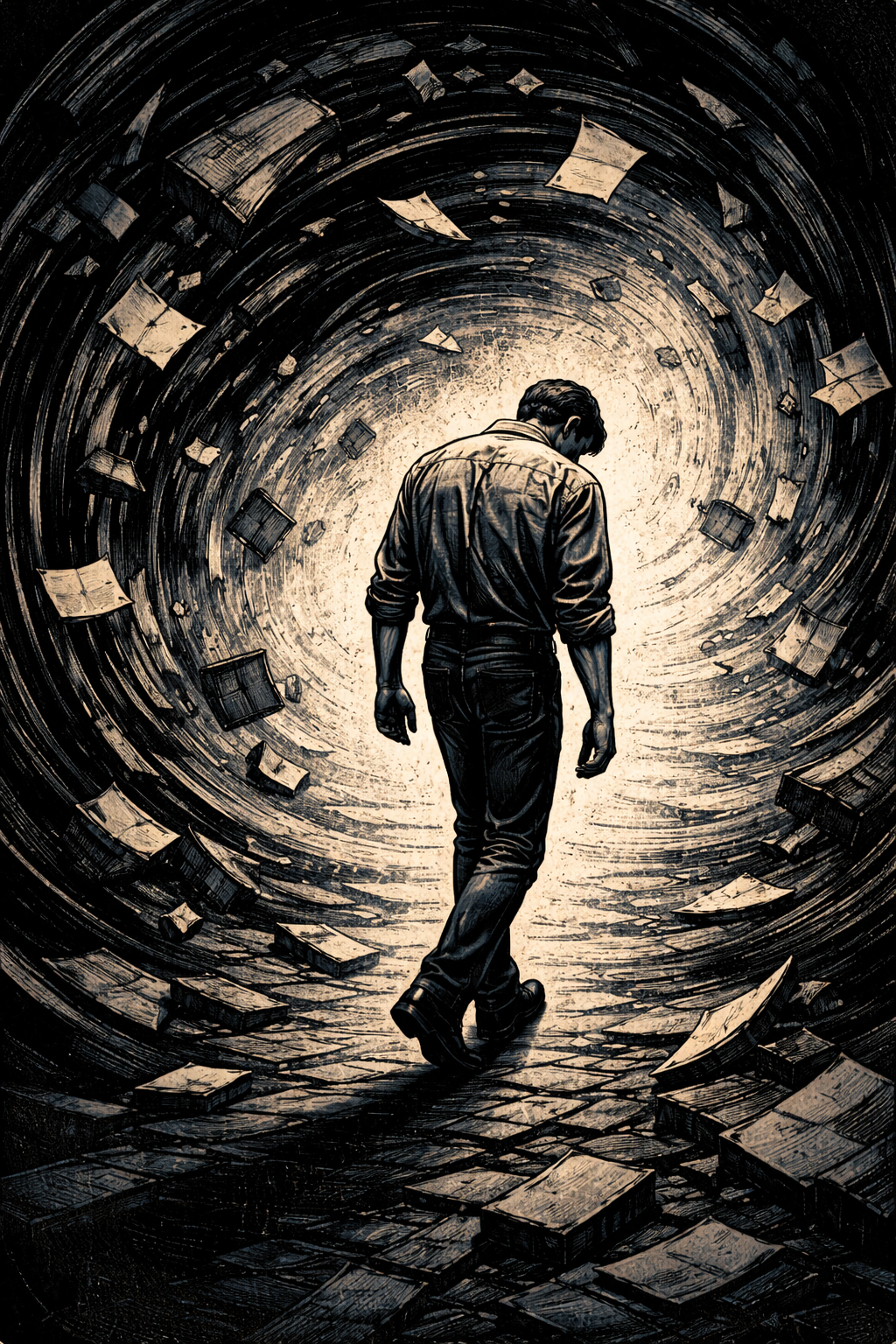

Over the past decade, and especially since the pandemic, that scaffolding has changed. Remote and hybrid work, high turnover, gig arrangements, and hustle culture didn’t just alter where work happens. They changed whether work still functions as a social place at all. Tasks remain. Meetings remain. Slack messages remain. But the relational residue, which we could also call the informal moments where familiarity turns into friendship, has steadily eroded. A portion of what we’re attributing to the loneliness crisis among men (and women) is a structural collapse of work as a third place (McCarthy et al., 2025; Littman et al., 2021).

What “Third Places” Do & The Role of Workplaces

Sociologists and community psychologists use the term “third places” to describe environments that sit between home and work: places where people show up regularly, interact without much effort, and feel socially safe without being emotionally exposed. Third places are not intimate by design. They don’t require vulnerability, deep disclosure, or even strong intention. What they offer instead is something more modest and more powerful, repeated, low‑stakes interaction that allows familiarity, trust, and belonging to accumulate over time (Littman et al., 2021).

For much of the twentieth century, we accessed these conditions outside of work through churches, unions, fraternal organizations, recreational leagues, neighborhood bars, or civic groups. As participation in these spaces declined, however, the need for regular, socially sanctioned connection did not disappear. It migrated. Quietly, and without much planning, work absorbed many of the functions those third places once served.

This mattered because men’s friendships often form through shared activity rather than explicit emotional exchange. You do something together like work on a project, solve a problem, overcome a micro-managing boss, and your connections develop in the background. Work provided exactly that: shared purpose, repeated contact, and a reason to keep showing up. Importantly, it did so without requiring men to name the interaction as “friendship” or perform emotional labor that might feel socially risky.

The belonging literature helps clarify why the workplace worked in this way. Belonging is not a feeling that appears on its own; it is produced through what scholars call belonging work—the ongoing process of participating, being recognized, and contributing within a shared social context (Kuurne & Vieno, 2021). From this perspective, friendship is best understood not as a personality trait or individual skill, but as a relational resource that depends on time, structure, and opportunity (Birmingham et al., 2024). Work didn’t replace friendship intentionally. It replaced it accidentally (Kuurne & Vieno, 2021; Birmingham et al., 2024).

What Breaks When Work Becomes Thin, Fragmented, or Transactional

Work doesn’t need to feel like a family. But it used to provide enough shared time and continuity for friendship to form in the background. When work gets thinner and reflects less shared space, more churn, more transactional exchange, connection doesn’t vanish overnight. It becomes harder to start and easier to lose.

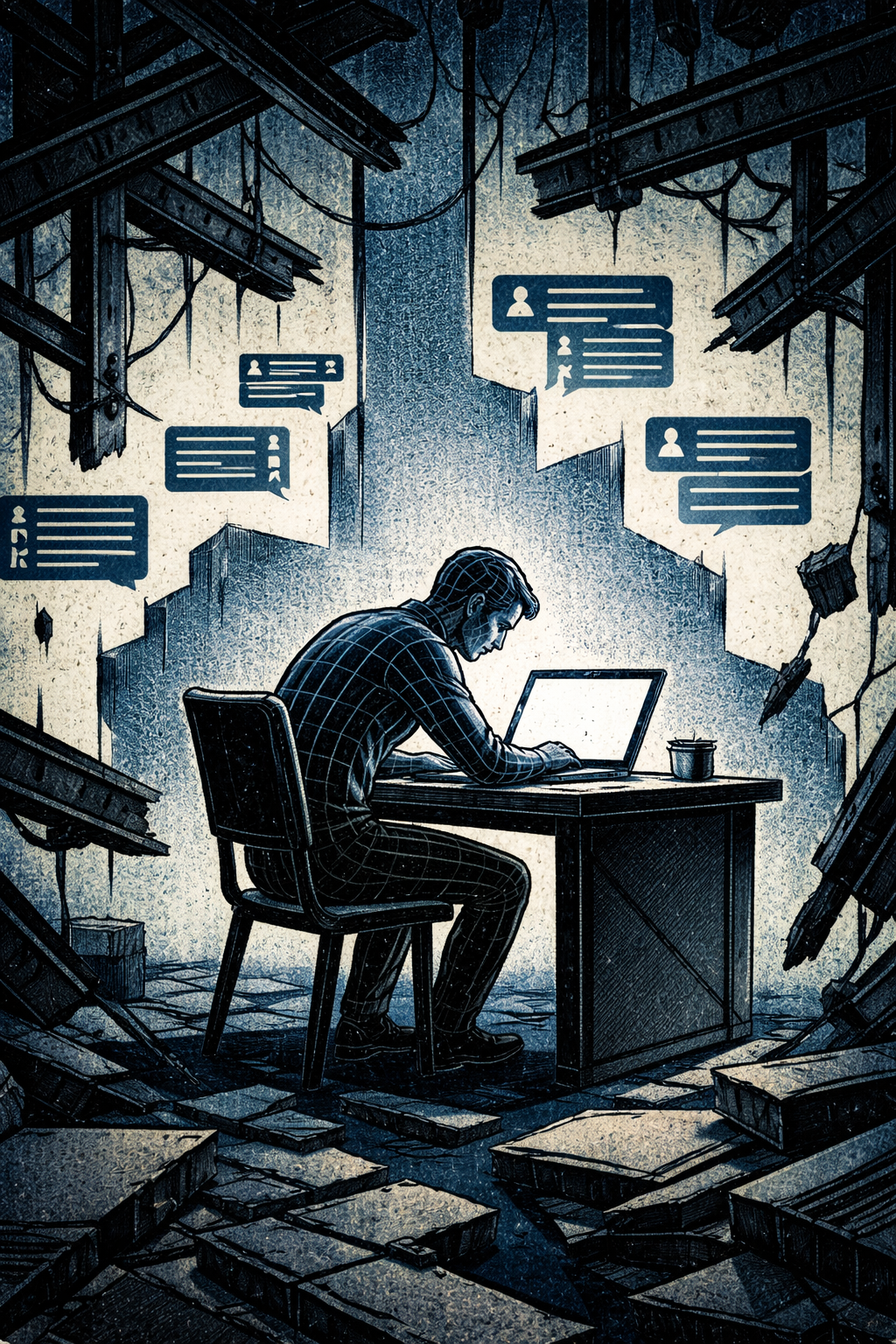

A. Remote and Hybrid Work: Connection Without Belonging

Remote and hybrid setups can preserve output while weakening the social “glue” that makes people feel known. The issue isn’t silence. Many remote teams communicate constantly. The issue is what remains: scheduled meetings and task updates that lack the informal cues of spontaneous, face-to-face moments.

That’s why loneliness can rise even with packed calendars. The research points to the concept of perceived isolation or disconnection, the gap between the connection people want and what work provides, as the core mechanism, not the sheer number of interactions (Adamovic, 2022; Cacioppo, et al., 2009; McCarthy et al., 2025). Hybrid work can worsen this when in-person days become meeting-heavy, leaving little room for casual connection (Barrero et al., 2023; Becker et al., 2022).

B. Turnover and Hustle Culture: The End of Relational Accumulation

Friendship needs time. High turnover, constant reorgs, and relentless pace reset the social clock before trust can build. In high-demand systems, that loss of relational buffer matters: workplace friendship can reduce exhaustion and protect well-being, but hustle and churn make it harder to do the ongoing “belonging work” that keeps relationships alive (Han et al., 2025; Kuurne & Vieno, 2021).

C. Gig and Contract Work: Work Without Membership

Gig and contract work thin connection by design. When work is organized around short-term tasks rather than membership, coworkers are temporary and community is optional. Reviews of gig work describe social isolation as a predictable adaptation when stable workplace relationships aren’t available (Russell et al., 2023).

Why This Matters for Men—and What Employers Are Missing

This isn’t about men being “bad at friendship.” It’s about where friendship tends to happen for men. When work stops providing that shared context, many men don’t lose friends in a dramatic way; they lose the default setting where friendship stays alive. This isn’t evenly distributed: older men can be hit hard as work ties thin while other roles shift (Dietz & Fasbender, 2022), and minority men may face added barriers when workplace culture does not reliably signal recognition and safety (Hutchings, 2024).

The health consequences are real. Work-related loneliness is linked to exhaustion, depressed mood, sleep problems, and disengagement (McCarthy et al., 2025; Beckel & Fisher, 2022). At the same time, workplace friendship can buffer stress and burnout, so when it erodes, demanding jobs become harder to sustain (Chen et al., 2024; Schutzmann et al., 2022).

Here’s the employer blind spot: many organizations act like relationships are optional and nice if they happen, irrelevant if they don’t. But the evidence suggests workplace friendship supports well-being, commitment, and engagement (Chen et al., 2024; Ozbek, 2018). When belonging thins, the costs show up as burnout and turnover, especially in high-pressure systems (Han et al., 2025; Schaechter et al., 2024). You can think of this as relational debt: work pulls effort and attention while shrinking the conditions that replenish connection.

Rebuilding the Social Ground of Work

Here’s the core claim: men’s loneliness is partly a work design problem.

For a lot of men, work became one of the last places where connection happened without planning. Not because work was warm, but because it provided shared time, shared purpose, and repeated contact. As those conditions thin, friendship doesn’t disappear because men stopped caring. It disappears because the structure that kept it easy quietly fell away.

So, the question isn’t whether work should be social. Work has always been social. The real question is whether we’re willing to design work to support belonging, instead of treating relationships as optional.

If we don’t, the costs won’t stay abstract. They will show up as burnout, disengagement, and worsening health, especially for men who relied on work as a primary place to belong.

References

Adamovic, M. (2022). How does employee cultural background influence the effects of telework on job stress? International Journal of Information Management, 66, 102513.

Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N., & Davis, S. J. (2023). The evolution of work from home. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 37(3), 23–50.

Beckel, J. L. O., & Fisher, G. G. (2022). Telework and worker health and well-being: A review and recommendations for research and practice. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 3879.

Birmingham, W. C., et al. (2024). Social connections in the workplace: A review and directions for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. Advance online publication.

Cacioppo, J. T., & Hawkley, L. C. (2009). Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 13(10), 447–454.

Chen, Y., et al. (2024). Meta-analytic structural equation modeling of workplace friendship, well-being, and organizational commitment. Work, 78(2), 345–360.

Dietz, L., & Fasbender, U. (2022). Age-diverse workplace friendship: A systematic literature review. Work, Aging and Retirement, 8(4), 239–255.

Gravett, K., & Ajjawi, R. (2022). Belonging as situated practice. Studies in Higher Education, 47(8), 1581–1593.

Han, S., et al. (2025). High performance work systems and employee performance: The roles of employee well-being and workplace friendship. Human Resource Development International. Advance online publication.

Hutchings, Q.R., (2024). Blackness preferred, queerness deferred: navigating sense of belonging in Black male initiative and men of color mentorship programs. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education. 37(5), 1425-1437.

Kuurne, J., & Vieno, A. (2021). Developing the concept of belonging work. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 51(3), 467–486.

Littman, A. J., et al. (2021). Third places, social capital, and sense of community as mechanisms of health promotion. American Journal of Community Psychology, 67(3–4), 325–339.

McCarthy, J. M., et al. (2025). All the lonely people: An integrated review and research agenda on work and loneliness. Journal of Management. Advance online publication.

Ozbek, M. F. (2018). Do we need friendship in the workplace? Journal of Economy Culture and Society, 57, 1–22.

Russell, Z. A., et al. (2023). The organizational psychology of gig work: An integrative conceptual review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 108(3), 307–334.

Schaechter, J., et al. (2024). Institutional culture of belonging and attrition risk among health care professionals. Journal of Women’s Health.

Sias, P. M., et al. (2012). Workplace friendship in the electronically connected organization. Human Communication Research, 38(3), 337–365.