From Talk to Transfer

How Male‑Engagement Curricula Deliver Relational Masculinity Content on Sexual and Reproductive Health

A workshop of buffaloes focused on sexual and reproductive health.

Content parallels presentation at the International Conference on Family Planning (ICFP) in Bogotá on 11/4/2025. All curricula reviewed below can be found at the Male Engagement Compendium. The original slide deck is located here.

Men’s health is having a cultural moment. Across social media and public debate, we see more conversations about how men can care for their bodies, manage stress, or build confidence. But much less attention is given to how men learn and practice, healthier relational behaviors, especially in the context of sexual and reproductive health (SRH). We spend far less time asking: Where do men learn to communicate clearly? To support a partner’s autonomy? Or, to navigate a medical visit?

In my work, I approach these questions through a relational masculinity lens. This perspective is built upon an understanding that masculinity becomes healthier when men build skills that strengthen relationships, not control them. I don’t frame all men as gatekeepers who need to be managed or as isolated individuals in need of “fixing.” We’re a diverse group with layers. Men are relational actors whose choices directly influence the wellbeing of partners, children, and communities.

On November 4, 2025, at the International Conference on Family Planning (ICFP) in Bogotá, I presented findings from a systematic review of ten male‑engagement curricula used across global SRH programs. “Three questions undergird the analysis: (1) How do these curricula teach gender and power? (2) How do they teach interpersonal communication? (3) How do they teach men to navigate the health system?”

Review Methods

Before describing the methods, it is helpful to locate this work within the broader evidence base. Many male‑engagement frameworks—including Program H, Many Ways of Being, Engaging Men in Family Planning guidance, and the Know–Care–Do model—emphasize that men learn best when interventions build awareness (Know), emotional motivation (Care), and behavioral capability (Do). The RAST model (explained below) parallels this trajectory by ensuring that reflection, analysis, practice, and real‑world transfer all occur.

To answer the questions, a structured, multi‑stage review aligned with the analytic process was conducted. First, every component of each curriculum—sessions, activities, facilitation notes, and participant materials were read. Then, relevant content—instructional language, scripts, prompts, activities, and artifacts—was pulled into a shared database and standardized across four analytic dimensions.

Depth: whether the activity moves beyond discussion toward practice.

Coverage: which topics across gender/power, communication, and health-system engagement are included.

Safeguards: how autonomy, confidentiality, consent, and GBV risk are handled.

Artifacts: what tangible tools participants take home.

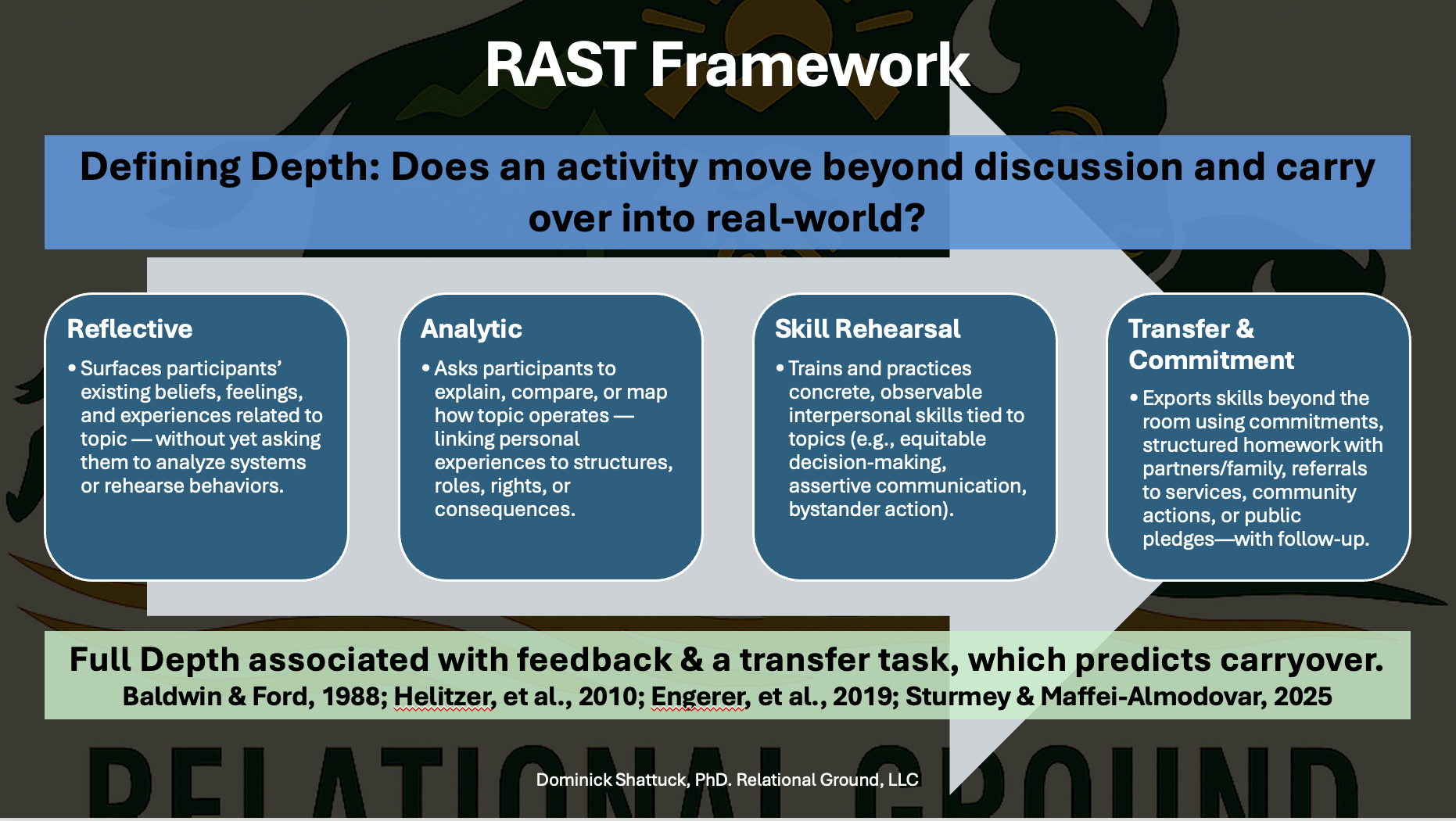

To assess a curriculum’s depth, we developed the R → A → S → T Framework, breaking instructional depth into four stages:

Reflective: Does the curriculum ask participants to engage emotionally and cognitively with a prompt, scenario, or lived experience? This stage opens the door to curiosity and self‑awareness.

Analytic: Are participants instructed to examine norms, power, and decision‑making patterns through structured questioning and facilitated discussion? This provides an opportunity to make meaning as a group from what surfaced during reflection.

Skill Rehearsal: Participants practice specific skills—for example, communication micro-skills, a conversation with a healthcare provider with coaching and feedback.

Transfer & Commitment: Vision-oriented activities are integrated that help participants identify concrete next steps, make a small commitment, or complete a take‑home task that carries learning outside the session.

Curricula that achieved full RAST depth, especially those combining Skill Rehearsal with Transfer & Commitment, were notably more likely to support real‑world behavior change based on project outcomes. This aligns with long-standing evidence that behavioral skills require not only understanding but practice, reinforcement, and opportunities for application.

Findings

A Note on Frameworks Used

The findings below integrate insights from global male‑engagement literature such as the Know–Care–Do model, the Male Engagement in Family Planning Indicator Brief, and gender‑transformative curricula including Program H, Program P, Journeys of Transformation, and Bandebereho. The domains below map closely to where instructional design either succeeds or falls short of providing a complete set of interpersonal activities. Together, they allow us to see not only what curricula teach, but how deeply they cultivate reflection, analysis, skill rehearsal, and transfer—the four stages required for meaningful learning under the RAST framework.

Gender Norms & Power

Gender norms and power are central to engaging men because they shape what men believe they are allowed to feel, say, and do in relationships. Across the literature of male engagement in reproductive health, there is an interest in providing men with the examples and opportunities to be more prosocial and empathetic toward their partners. Often, this is framed in the context of “harmful male behaviors”. This analysis understands there is diversity in men’s lived experiences, their expectations of relationships, parenting, and shared decision-making. Generally, the normative activities in these curricula promote prosocial, equitable, and thoughtful engagement among men in partnership. Promoting these interventions is not done to “fix” men.

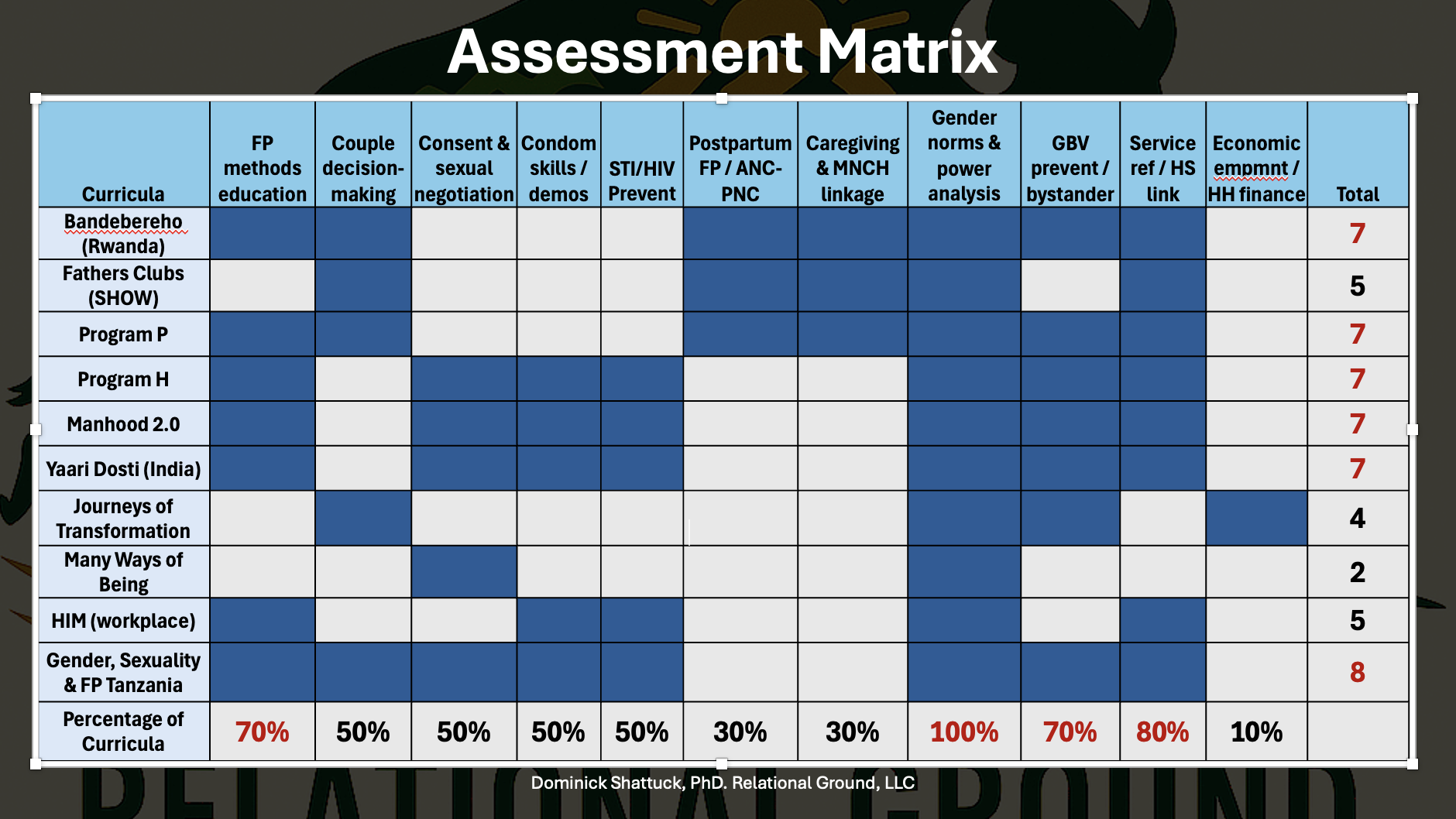

Each curricula was assessed across eleven criteria. Blue boxes reflect topics that were addressed in each. Note: The goals of some curricula did not include all topics.

Reproductive health conversations are not common among men, either in interpersonal conversations or at the doctor’s office. As a result, responsibilities have traditionally fallen upon women. These patterns do not simply influence attitudes; they constrain the skills men are willing or able to practice. When programs create structured opportunities for men to reflect on and analyze these norms, they open space for new relational possibilities. Men examine how power operates in everyday interactions, how it affects autonomy within relationships, and how healthier relationships exhibit shared responsibility, empathy, and respect from both partners. This makes work on gender norms and power not just a technical component of male engagement, but a necessary foundation for building stronger relationships.

Within this review, every curriculum addressed gender norms and power dynamics, but the quality and depth varied widely. About half satisfied the requirements of the RAST framework, while the rest remained in the Reflective or Analytic stages. Most often, the limited curricula did not integrate practice and rehearsal of the topic with men. About 70% addressed family planning (FP) decision‑making, method choice, or bystander action. Encouragingly, eight out of ten curricula included language related to safeguarding their partners’ health-related autonomy and GBV referral cues. Some curricula offered structured artifacts (e.g., worksheets, scripts, at-home exercises), suggesting a greater likelihood of learning transfer.

Activities to Consider for Gender Norms & Power:

Power Mapping (Program H; Journeys of Transformation)

Participants diagram who makes which decisions at home, followed by facilitator‑led analysis. Helps reveal invisible power patterns and opens discussion about shared decision‑making.“Moment of Choice” Scenarios (Bandebereho Session 5; Program P Module 1)

Small groups analyze a scenario in which a man faces a decision that affects his partner. They identify coercive versus autonomy‑affirming responses and rehearse the healthier option.Norms Continuum Exercise (Program H Session 2; Many Ways of Being “Masculinity Spectrum”)

Participants place common gender norms on a spectrum from harmful to equitable, followed by analytic discussion of consequences for partners, couples, and communities.Bystander Micro‑Practice (Program H; Yaari Dosti)

Men practice short interventions—disagreeing with a harmful comment, redirecting a conversation, or checking in with a peer. Builds confidence in relational accountability.Equitable Decision‑Making Drills (Program P Session on Joint Planning; Program R)

Paired rehearsal where participants practice asking open questions, sharing information, and deferring to a partner’s preference. Reinforces autonomy and shared responsibility.

Relational masculinity insight: Men benefit from practicing how to support autonomy and de‑escalate conflict. These skills help turn relational intent into relational safety for both individuals in the relationship.

More AI generated buffaloes working through some communication activities.

Communication Skills

Communication sits at the center of relational masculinity because it is the mechanism through which intentions become visible, and accountable. Many boys, though not all, gradually lose communication skills as gender socialization teaches them to suppress a wide range of emotional expressions (e.g., fear, sadness, compassion, and vulnerability), while reinforcing autonomy, stoicism, competition, and self-reliance as normative masculine traits. As they internalize these norms, they increasingly avoid prosocial behaviors and intimate, face-to-face communication, often out of fear of ridicule or social punishment for appearing “girly” or emotionally expressive. Over time, this social pressure limits their practice of key relational skills (e.g., empathy, emotional literacy, and active communication) resulting in a progressive narrowing of their communicative abilities and a decline in the quality and intimacy of their relationships (friendships and romantic) as they navigate adolescence (Shattuck, 2024). The literature consistently shows (e.g., Program H, Manhood 2.0, Journeys of Transformation) that men benefit most when communication instruction moves beyond discussion and into guided practice. Without rehearsal, men may understand concepts intellectually but remain unable to use those skills in emotionally charged moments.

In our review of the communication skills development activities, half of the curricula reached full RAST depth, meaning they combined reflection, analysis, rehearsal, and transfer. About 40% assigned at‑home or couple-based tasks, which aligns with the Know–Care–Do framework and highlights that skills become durable only when practiced in real settings. At least 60% taught four or more communication micro‑skills, such as I‑statements, reflective listening, FP dialogue, and consent‑oriented bystander approaches. Programs that incorporated rehearsal tended to include stronger safeguards as well, reinforcing ethical engagement.

Activities to Consider for Communication Skills:

I‑Statement Rehearsal (Manhood 2.0 Session 3; Program H Communication Module)

Participants convert blame‑focused statements into calm I‑statements, practicing tone, body language, and clarity. Supports relational safety.Reflective Listening Rounds (Many Ways of Being; Journeys Session on Dialogue)

Triads rotate through speaking, listening, and observing roles. Facilitators guide men to reflect key ideas without judgment.FP/Contraception Dialogue Practice (Program P Visit Plan Exercise; Engaging Men in FP Guide)

Structured role‑plays where men practice asking questions, acknowledging partner preferences, and avoiding directive language.Consent & Boundary‑Setting Scripts (Program H; Manhood 2.0 Consent Unit)

Short drills where men rehearse asking for consent, responding to hesitation, and affirming autonomy.De‑Escalation Micro‑Scenarios (Journeys; Many Ways of Being “Cooling the Heat”)

Facilitator reads a conflict cue. Participants practice pausing, grounding, and re‑entering with curiosity.“Two Good Questions” Practice (Program P; Bandebereho)

Participants generate two respectful questions to ask a partner or provider, supporting shared understanding and reducing assumptions.

Program developers may also pilot Niobe Way’s seven-step transformative-interviewing technique; it builds communication skills and addresses gender-and-power dynamics (Way, 2024).

Relational masculinity insight: Communication is a practice domain, not a knowledge domain. Men need repeated rehearsal and supportive feedback to develop reliable relational skills.

A community of buffaloes co-designing the male engagement program.

Men & the Health System

Engaging men within the health system requires clarity of role, skillful communication, and safeguards that prevent gatekeeping. In the curricula that were reviewed, most curricula focused on men’s participation to improve partners’ SRH outcomes. Programs such as Program P, Bandebereho, and the Male Engagement Indicator Brief highlight that men often enter clinical settings without guidance on what supportive behavior looks like. Without explicit instruction, they may unintentionally dominate conversations or overstep, even when motivated by care.

The curricula reviewed reflect this range of challenges. About 40% of curricula positioned men as visiting health services as partners, 35% as clients, and 20% addressed both. Eight out of ten curricula taught at least three provider‑interaction skills that included: asking questions, clarifying side effects, establishing consent, or negotiating accompaniment. These align with global best practices for supporting men’s constructive participation in SRH.

Decades of health development work reflect the benefits of service linkages. Across the ten curricula reviewed, only two achieved in-depth linkages (e.g., structured visit plans or integrated provider/CHW participation). Three provided less structured approaches (referrals or scripts), while the remainder offered limited or no explicit guidance on how men should navigate services.

Activities to Consider for Men & the Heath System:

Co‑Delivery with CHWs or Providers (Bandebereho Sessions 7–9)

CHWs integrate into group sessions; men ask questions, learn where services are offered, and receive real‑time clarification—an example of a strong linkage to services.Structured Visit Plan (Program P Module on Accompaniment)

Men complete a step‑by‑step visit plan: what to ask, how to introduce themselves, how to affirm autonomy, and what follow‑up is appropriate. This activities can help men be supportive in their partners’ or better enabled in their own health visits.Provider‑Dialogue Q&A (Manhood 2.0 with Optional Clinician Visit)

A clinician joins for Q&A, answering method questions and modeling respectful dialogue. The activity breaks the barrier between health care provider and patients. It also enables men to benefit from group members asking questions they may not think of on the day of the clinical visit.Rights + Service Signposting (Journeys of Transformation “What Does the Law Say?”)

Participants learn relevant rights and receive signposting to clinics, hotlines, or CHWs—aligning with moderate linkages to care.Accompaniment Micro‑Practice (Program P; Engaging Men in FP Guide)

Participants rehearse supportive accompaniment behaviors (e.g., “Would you like me to join you, or would you prefer to go alone?”), ensuring autonomy is centered. It may seem elementary, but sometimes this is the first door that needs to be opened in a larger conversation about health.[1]

Relational masculinity insight: When men understand their role and rehearse supportive provider‑dialogue, they are more likely to engage clinics without overshadowing partners or exerting pressure. When men rehearse provider‑dialogue and know their role—Client or Partner—they can participate in care without overshadowing or controlling others. Across all domains, these activities operationalize relational masculinity by giving men structured practice, supportive feedback, and tools that help them carry skills into real‑world settings.

This buffalo prepares and then attends his doctor’s appointment. It looks like his doctor is a donkey. This was a choice of the AI. :)

Minimum Viable Package (MVP) for Practitioners

Some practitioners may jump to this section. Central to this process, and discussed below, is knowing who the men are that you are trying to reach, what their experiences are, what their concerns and hopes are, as well as how they vary across the population. Below I offer a Minimum Viable Package—the smallest set of actions that still produce meaningful instructional depth for reproductive health programming.

A strong MVP includes:

One activity + one artifact per domain (Gender/Power, Communication, Men & the Health System).

Delivery at full RAST depth—Reflective → Analytic → Skill Rehearsal → Transfer & Commitment.

Rehearsal of at least three provider‑dialogue scenarios.

Safeguards: autonomy line, confidentiality language, and GBV referral pathway.

At least two service linkages, with a way to track whether they lead to visits.

This approach ensures “depth with portability,” meaning the learning reliably travels into real interactions.

Standards for Designing New Projects

Effective MVPs and new male-engagement projects must be grounded in local realities and refined through iteration. Activities on norms, communication, and health-system navigation should reflect local values and relationship expectations, actual household decision-making, clinic structures and provider attitudes, and men’s and women’s SRH priorities. Curricula resonate when participants recognize themselves and their partners in scenarios—hence the importance of co-design with CHWs, women’s groups, youth leaders, and fatherhood networks. Because men are not a monolith, programs should pilot, gather structured feedback, and adjust: mirror local family structures; use familiar language for relationships, methods, and rights; model realistic clinic interactions; avoid shaming; integrate locally credible examples of relational masculinity; and check with women’s and youth advisors to prevent harm. Even small pilots reveal whether examples land, autonomy is protected, and unintended risks emerge, allowing refinement of language, scenarios, and the RAST progression.

Within this adaptive approach, evidence-based design standards apply:

Depth: Core activities reach full RAST depth.

Roles & Rights: Clearly mark when men act as Clients or Partners; embed consent and confidentiality.

Skills: Include provider-interaction skills and communication micro-skills.

Linkages: Start at D2 and mature toward D3.

Artifacts: Produce a practical takeaway each session.

Safeguards: Use autonomy-affirming language and GBV/confidentiality cues.

Grounded, tested, and iterative design makes interventions safer, more ethical, and more likely to change behavior.

Looking Ahead

Relational masculinity becomes real through a structured sequence based in adult-learning methodologies: Reflective → Analytic → Skill Rehearsal → Transfer & Commitment. When male-engagement programs consistently reach this depth, men develop the skills to communicate with care, support autonomy without overstepping, and navigate the health system responsibly. But this is also the moment to push the field further: the field should shift curricula to explicitly promote men’s own health-seeking—especially for SRH. Programs should add concrete, low-barrier modules that help men act as clients: mapping local services; practicing appointment calls; rehearsing rights, consent, and confidentiality language; troubleshooting costs, transport, and privacy; and using tools like Visit Plans, referral cards, and provider-dialogue scripts. Content should normalize preventive care (STI/HIV testing, condoms and correct use, vasectomy counseling and referral, fertility concerns, mental health, substance use, and chronic-disease checks), while guarding against gatekeeping or partner-control dynamics.

These findings also point to a clear next step: test these instructional approaches more rigorously and at scale, both in community settings and across the media and communication channels where men already spend their time. That means experimenting not just with group curricula, but with all the tools that are at our disposal: social-media series, short-form videos, interactive apps, SMS pathways, radio dramas, podcasts, long-form interviews, documentaries, fictional films, and story-driven mini-series that embed relational-masculinity cues and model autonomy-affirming communication. These platforms reach men who may never join a group session, including men in rural areas, men working long hours, men who distrust health services, and men whose identities or ages are under-represented in traditional interventions.

To engage the full diversity of men, we need diversified messaging and rapid iteration: short pilots, A/B tests, community feedback cycles, and partnerships with local creators to learn what resonates, what falls flat, and what unintentionally reinforces harmful norms. This is the future of relational-masculinity work: a field willing not only to teach in classrooms, but to learn from audiences, adapt quickly, and scale approaches that help men practice healthier relational behaviors and proactively seek care. I invite you to explore the full slide deck, experiment with one of the signature activities, and share how you adapt tools. Moving from talk to transfer, and from transfer to meaningful relational and health-seeking change is how we strengthen SRH outcomes for everyone.

Some of the tools to better engage men in SRH services.

References

CARE International Rwanda, & Promundo. (2012). Journeys of Transformation: A training manual for engaging men as allies in women’s economic empowerment. Kigali, Rwanda: CARE International Rwanda and Promundo.

Equimundo. (2023). Many Ways of Being: A curriculum for boys and young men (2-hour sessions). Washington, DC: Equimundo.

Extending Service Delivery (ESD) Project. (2010). Healthy Images of Manhood (HIM): Toolkit/guide for engaging men. Washington, DC: USAID/ESD.

Instituto Promundo, ECOS, Salud y Género, & PAPAI. (2002). Program H: Working with young men to promote gender equity in health. Rio de Janeiro/São Paulo: Instituto Promundo et al.

Plan International Canada. (n.d.). Fathers’ Clubs manual (SHOW project). Toronto, Canada: Plan International Canada.

Population Council/Horizons, CORO for Literacy, MAMTA, & Instituto Promundo. (2006). Yaari Dosti: Young men redefine masculinity—A training manual. New Delhi: Population Council.

Promundo-US. (2018). Manhood 2.0: A curriculum promoting a gender-equitable future of manhood. Washington, DC: Promundo-US.

Promundo-US, CulturaSalud, & REDMAS. (2013). Program P: A manual for engaging men in fatherhood, caregiving, and maternal and child health. Washington, DC & Rio de Janeiro: Promundo-US, CulturaSalud, and REDMAS.

RWAMREC (Rwanda Men’s Resource Center), & Promundo. (2015). Bandebereho: A program engaging men in reproductive and maternal health and violence prevention—Facilitator’s manual. Kigali, Rwanda: RWAMREC and Promundo. [Manual not in current upload set; citation provided for completeness.]

Schuler, S. R., Nyagah, F., & Gay, J. (2011). Facilitator’s manual for discussions on gender, sexuality, and family planning in rural Tanzania. Washington, DC: C-Change/USAID.

Shattuck, D., Wilkins, D., Davis, K., McLarnon, C., Pulerwitz, J., Betron, M., Waiswa, P., Gottert, A., & Mwaikambo, L., on behalf of the Male Engagement Task Force (METF), USAID Interagency Gender Working Group (IGWG). (2024). Building bridges: Promising strategies to improve the health of boys and men by promoting social connection and support. Washington, DC: Interagency Gender Working Group.

Way, N. (2024). Rebels with a cause: Reimagining boys, ourselves, and our culture. New York, NY: Dutton.

[1] Linkage Footnote:

Weak service linkage: Light, informational signposting (e.g., “services exist at X clinic”). No structured referral, script, or provider connection. Typically occurs verbally or in a single slide or handout.

Standard service linkage: Structured referral or service‑navigation support (e.g., providing a questions script, a referral slip, a service directory, or explicit signposting embedded in an activity). Participants know where to go and what to ask, but the program does not coordinate contact with the health system.

Robust service linkage: Strong, embedded linkage (e.g., co‑delivery with CHWs or providers, structured visit plans, facilitated introductions, or coordinated clinic engagements). These programs link the instructional space to the service environment and typically includes rehearsal of provider‑dialogue plus a concrete pathway into care.