General Who? What White Christmas Teaches Us About Men, Aging, and Being Loved

White Christmas main cast: Bing Crosby, Danny Kaye, Rosemary Clooney, and Vera-Ellen.

Every Thanksgiving, before the football games start and the food coma hits, my family puts on White Christmas. It kinda kicks off the Christmas season in our house.

It’s background noise at first. I’m moving around the house, helping with food prep, catching a few minutes on the couch, hearing Bing and Danny croon from the other room. I’ll pop in for favorite bits—the opening war scene, the weird choreography dance, and, of course, men performing the ridiculous “Sisters” number in blue feathered costumes.

But every year, something different grabs my attention. Less the Technicolor charm of 1954, and more how the men in this movie talk about love, loyalty, and care with almost zero self-consciousness. Bob, Phil, and the other soldiers are allowed to be openly devoted to “the old man,” General Waverly. And I can’t help wondering: what’s happened in the 70 years between that version of masculinity and the one most men inhabit now?

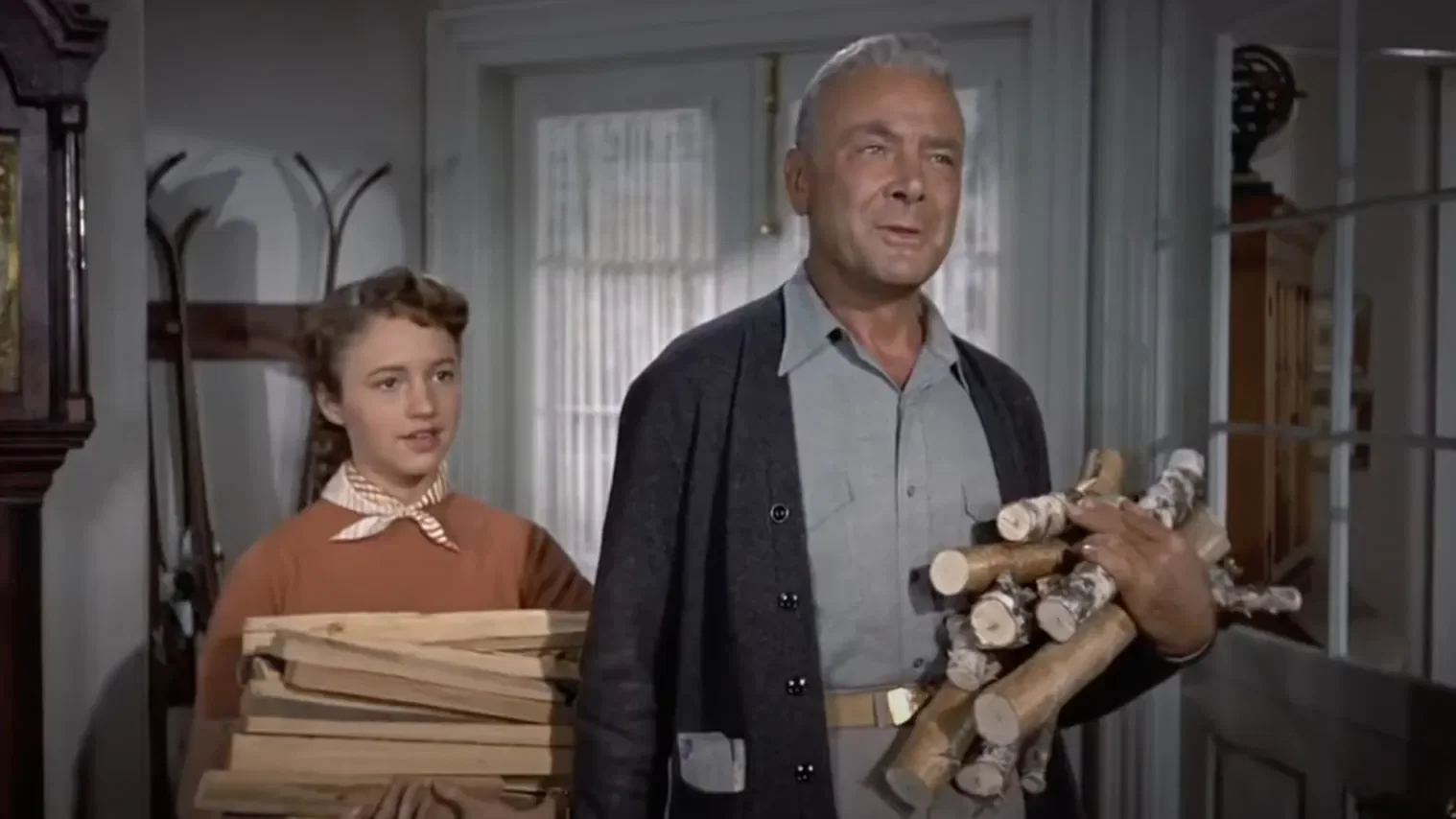

General Waverly and his daughter

A story about men caring for men

Quick refresher on the plot: Bob Wallace and Phil Davis are former WWII buddies turned song-and-dance partners. You can let that settle in, for starters. They stumble on the fact that their old commanding officer, General Waverly, is running a struggling inn in Vermont. The bookings are thin, the snow won’t fall, and the old man is quietly going broke. So they decide to do what they know best—stage a big Christmas show to fill the place and help him out.

Yes, there’s romance in the movie, but the emotional backbone is men caring for men: soldiers for their general, buddies for each other, a community rallying around an aging leader. And because it’s basically a Broadway-style musical on film, the men get to sing, joke, dance, and be emotionally connected in ways we almost never see in “serious” male roles.

“We’ll Follow the Old Man”: Unembarrassed devotion

One of the most striking scenes comes early, in the war. It’s General Waverly’s last day in command. The men surprise him with the song “We’ll Follow the Old Man”—essentially a platonic love letter in uniform.

They sing:

We’ll follow the old man wherever he wants to go…

Because we love him, we love him…

There’s no wink, no irony, no nervous laughter. Just a group of soldiers singing, with full-throated sincerity, that they love this man.

I watch that now and think about how rare this is on screen today: a group of men telling another man “we love you” without it becoming a punchline. Such punchlines are frequent in the shows we watch (i.e., Friends), which contain plenty of genuine moments of connection between male characters, often undercut with homophobic jokes or awkwardness. The message was clear: male affection is funny, suspect, or something you have to immediately laugh off.

In White Christmas, the affection is the point. Waverly is admired not just because he outranks them, but because he keeps them steady, keeps them safe—keeps them “on the ball.” Leadership is explicitly relational.

This song and act is a time-capsule of mid-century humor.

“What Can You Do With a General?”: Aging and male vulnerability

Later in the film, we see the other side of that story. Waverly is retired, under-employed, and increasingly invisible in the civilian world. He has gone from “the old man” everyone would follow into battle to “General who?”

The song “What Can You Do With a General?” puts words to his fear:

They fill his chest with medals while he’s across the foam

…The next day someone hollers when he comes into view

“Here comes the general” and they all say “General who?”

It’s a surprisingly sharp meditation on what happens when a man’s identity is fused to his role—and the role disappears. One day you’re the person everyone salutes; the next, you’re just an old guy running a failing inn.

Bob and Phil’s response is deeply tender. They don’t tell him to “toughen up” or “stop living in the past.” Instead, they mobilize their entire professional lives to restore his sense of meaning and dignity. They bring back his old unit, fill the inn with people who remember him, and stand him up in front of a room that still knows his name.

The film doesn’t just acknowledge his loss; it organizes community care around it.

Half-way through the movie, there is this random dance routine about choreography. About as meta as things got in the 50’s.

What changed in 70 years?

White Christmas came out in a post-war moment when male camaraderie was both idealized and normalized. Men had lived and died together in trenches and camps. That closeness shows up in the movie as singing together, teasing each other, and stating loyalty out loud.

History has taught us that post World War II masculinity was far from a completely prosocial and open communication setting for men. Countless men returned with trauma, scared from the horror of war. Within the movie, General Waverley’s day-to-day management of his financial stress was to shield this reality from his two loyal soldiers, maintaining his stoic presentation.

Yet, in the decades that followed, the dominant script for heterosexual masculinity narrowed: more emphasis on toughness, distance, and self-reliance; less room for song-and-dance men who unabashedly tell another guy, “I love him.” Saying that out loud started to require armor—usually in the form of a joke.

In my work on men’s health, I see the fallout of that narrowing. Connection and social support are tied to health and wellness. We know that isolation, emotional suppression, and reluctance to seek help contribute to higher rates of suicide, substance use, and earlier mortality among men. It’s not that men are less emotional. It’s that they’re trained to hide emotion, especially tenderness toward other men, until it shows up sideways—as anger, withdrawal, or risk-taking.

Watching White Christmas, I find myself wondering: did we trade in something essential—this open, musical, shameless affection—for an even thinner, lonelier idea of what it means to be a man?

General Waverly thanking Bob and the troops.

What these old songs ask of us now

Back on my Thanksgiving couch, my family is half-watching. The turkey is in the oven, someone’s asking when the game starts, and on screen a roomful of old soldiers are singing:

Because we love him, we love him…

I’m not just watching a Christmas movie. I’m watching an older script for how men could show up for each other with loyalty, vulnerability, and concrete action when another man is struggling.

We need more of that. More spaces where men can say “I love you” to the “old men” in their lives—fathers, uncles, coaches, mentors, pastors—and have it land without embarrassment. More room for guys like Waverly to admit, “I don’t know who I am without the uniform,” and have friends who respond with a plan and a chorus, not silence.

So here’s a small experiment for this season:

Find the “old man” in your life and using the worlds that feel most natural to you, and tell him you love him this holiday season.