Why Gestalt Psychology and the Relational Ground?

AI image of people in a community center.

Finding Connection in a Disconnected World

In today’s world, rates of friendship are declining, and loneliness is on the rise. Many people feel isolated, disjointed, and overwhelmed by the pace and complexity of modern life. Gestalt Psychology, with its focus on seeing patterns and relationships, offers an important way to understand and address these challenges. At its core, Gestalt teaches us that “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” This means that our experiences, relationships, and communities can’t be understood by looking at individuals in isolation. Instead, they must be viewed as interconnected, dynamic wholes (Koffka, 1935; Wertheimer, 1923).

I find this perspective directly relevant to our current struggles with loneliness and disconnection. By focusing on the links between people, their environments, and society, Gestalt Psychology provides frameworks for rebuilding relationships and fostering community. This is why it aligns so closely with the ideas behind Relational Ground, which emphasizes that human well-being emerges from meaningful connections with others and the world around us.

Foundations of Gestalt Psychology

Historical Origins

Gestalt Psychology began in Germany in the early 1900s with three key figures: Max Wertheimer, Kurt Koffka, and Wolfgang Köhler. They were fascinated by how people make sense of their world. For instance, when you listen to a song, you don’t hear separate notes — you hear a melody, a complete experience that is greater than its parts. This simple example captures the heart of Gestalt thinking.

At that time, psychology was dominated by two other approaches structuralism and behaviorism. Structuralism focused on breaking the mind down into its smallest pieces, like sensations or images, much like a chemist studying elements in a lab (Wertheimer, 1923; Ash, 1998). Behaviorism, on the other hand, ignored inner experiences and looked only at external behaviors, like habits or reflexes (Baars, 1986). While both had value, they failed to explain the richness of human relationships, emotions, and meaning.

Gestalt psychologists believed that to understand people, we must look at patterns and context, not just isolated elements. A powerful example of this comes from Wertheimer’s research on the phi phenomenon, where viewers see continuous motion in a series of still images, like how movies work today (Wertheimer, 1912). The mind creates motion and meaning, showing how we actively build a coherent whole from separate pieces.

Key Concepts and Everyday Applications

As Gestalt ideas spread, they influenced how we solve problems, learn, and relate to others. Wolfgang Köhler’s studies with chimpanzees revealed that learning often happens through insight, or those “aha!” moments when a solution suddenly becomes clear (Köhler, 1925). This is the same process we experience when a difficult problem finally clicks.

In education, teachers began using Gestalt principles to help students connect ideas instead of just memorizing facts (Metzger, 2006). In mental health, Fritz Perls developed Gestalt Therapy, which focuses on helping people become more aware of their present experiences and relational patterns. This approach is still used to address anxiety, depression, and relational trauma (Corey, 2021).

Even design and technology reflect Gestalt principles. Websites and apps use visual cues to guide attention, like making important buttons stand out. The FedEx logo’s hidden arrow is a classic example of how our minds create meaning through visual relationships (Ware, 2013). You can make your own conclusion about the Amazon logo.

When Nazi persecution forced Gestalt psychologists to flee Germany, they brought these ideas to the United States, where they influenced fields as diverse as public health, education, and therapy (Ash, 1998).

Kurt Lewin

Action Research and Gestalt Psychology

Action research is a practical, hands-on approach to studying and improving communities, organizations, and systems. This approach was first formalized by Kurt Lewin, one of the most influential Gestalt psychologists, who is often considered the father of action research. Lewin believed that research should not just study problems but also be part of solving them, especially in real-world contexts where people are directly impacted.

Action research aligns well with Gestalt Psychology because it focuses on understanding patterns and relationships while directly involving people in the process of change. In action research, the researcher and participants work together to identify problems, test solutions, and reflect on outcomes. This method is particularly effective for addressing issues like loneliness and declining friendships because it creates opportunities for genuine connection and shared learning. You can see these principles spread throughout current research by The Listening Project (Way & Nelson, 2018).

Lewin’s ideas have also influenced modern approaches like human-centered design, which similarly emphasizes collaboration, empathy, and iterative problem-solving. Both approaches value listening to the voices of those affected, co-creating solutions, and viewing change as a dynamic process. For example, a project might examine how a local health center could better support men's mental health. Instead of just surveying individuals, action research would engage men, families, and health professionals in a cycle of dialogue, planning, and action, creating an environment where new solutions emerge from the relationships themselves. This is very similar to how human-centered design teams create prototypes and test interventions in partnership with the community.

Core Principles of Gestalt Psychology

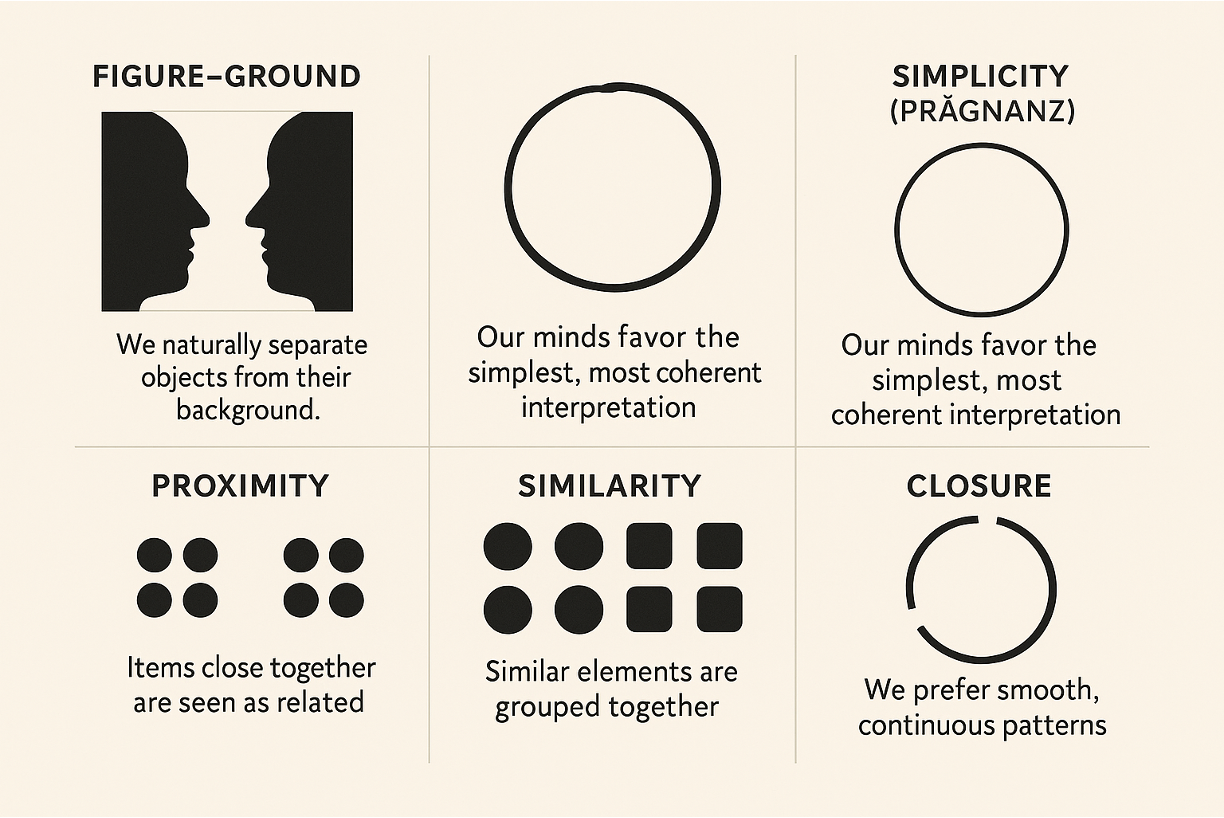

Figure-Ground: We naturally separate objects from their background (Rubin, 1915).

Simplicity (Prägnanz): This principle, introduced by early Gestalt psychologists like Wertheimer (1923), suggests that our minds naturally try to simplify complex images and experiences into the simplest, most coherent interpretations. Often, this is managed through Grouping Principles:

Proximity: Items close together are seen as related.

Similarity: Similar elements are grouped together.

Continuity: We prefer smooth, continuous patterns.

Closure: Our minds fill in gaps to see complete shapes (Koffka, 1935).

These principles help explain how we perceive the world and why relationships and context are so important.

Kurt Lewin and Field Theory

Kurt Lewin expanded Gestalt ideas to include social relationships and group behavior. He introduced a simple but powerful formula:

B = f(P, E)

Behavior is a function of the Person and the Environment (Lewin, 1936).

This means that to understand someone’s actions, you must consider both who they are and the environment they live in. For example, if someone stops exercising, it’s not just about motivation. Maybe they lack access to safe parks or social support. Lewin’s field theory visualizes life as a map filled with goals, needs, and barriers.

One of his students, Bluma Zeigarnik, discovered the Zeigarnik Effect — we remember unfinished tasks better than completed ones (Zeigarnik, 1927). This explains why lingering conversations or unresolved conflicts stay in our minds.

Gestalt Psychology and Health in Today’s World

Gestalt concepts are especially helpful for addressing today’s health challenges:

Clear Communication: Health messages designed with Gestalt principles are easier to understand (Noar et al., 2020).

Health-Seeking Behaviors: Our choices depend on personal beliefs, relationships, and environmental factors.

Mental Health: Gestalt Therapy helps people explore how loneliness, family patterns, and societal expectations impact well-being (Corey, 2021).

Community Health: Programs that address both individual needs and community support — like safe spaces for exercise — are more effective (Walker et al., 2019).

Why This Matters Now

Today, many people feel disconnected and alone. Social media, while connecting us digitally, often leaves us feeling more isolated. The Surgeon General has described loneliness as a public health epidemic, with effects on health comparable to smoking fifteen cigarettes a day. Research shows that strong friendships improve happiness, reduce stress, and even help people live longer. However, as highlighted in recent writings, the number of close friendships has steadily declined, especially among men. Boys often grow up wanting and needing emotional connection, but over time cultural pressures discourage these behaviors and they become less likely to share feelings or reach out for support.

Gestalt Psychology reminds us that humans thrive in connection — with friends, families, communities, and even physical spaces. By viewing health and relationships as part of a larger whole, we can design programs, policies, and personal practices that rebuild these essential bonds. Practical strategies from current public health programs highlight the value of cultivating empathy, improving communication skills, and creating safe spaces for men to connect shoulder-to-shoulder. These approaches help people practice relational skills and fight the isolation that many are feeling today.

For men, making space for conversations about reproductive health, mental well-being, and fatherhood can also create ripple effects in families and communities. As some of the blogs have discussed, when fathers openly talk with their children about sex, relationships, and health, it strengthens bonds and empowers future generations. Gestalt Psychology’s focus on wholes rather than isolated parts shows us that these conversations are not just about one individual, but about the health of entire communities. By bringing people back into meaningful relationships, we can counter the rising tide of loneliness and create a more connected, resilient society.

References

Ash, M. G. (1998). Gestalt Psychology in German Culture, 1890–1967. Cambridge University Press.

Baars, B. J. (1986). The Cognitive Revolution in Psychology. Guilford Press.

Corey, G. (2021). Theory and Practice of Counseling and Psychotherapy (10th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Koffka, K. (1935). Principles of Gestalt Psychology. Harcourt, Brace and Company.

Köhler, W. (1925). The Mentality of Apes. Harcourt, Brace and Company.

Lewin, K. (1936). Principles of Topological Psychology. McGraw-Hill.

Metzger, W. (2006). Laws of Seeing. MIT Press.

Noar, S. M., Bell, T., Kelley, D., Barker, J., & Yzer, M. C. (2020). Perceived message effectiveness as a predictor of health behavior and health communication outcomes. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 54(3), 226–239. https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/kaz054

Rubin, E. (1915). Synsoplevede Figurer. Copenhagen: Gyldendalske Boghandel, Nordisk Forlag.

Walker, R. J., Smalls, B. L., Hernandez-Tejada, M. A., Campbell, J. A., & Egede, L. E. (2019). Effect of diabetes self-management education on quality of care in low-income adults with Type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 42(3), 432–448. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc18-1605

Ware, C. (2013). Information Visualization: Perception for Design (3rd ed.). Morgan Kaufmann.

Way, N., & Nelson, J. D. (2018). The Listening Project: Fostering Connection and Curiosity in Middle School Classrooms. In N. Way, A. Ali, C. Gilligan, & P. Noguera (Eds.), The Crisis of Connection: Roots, Consequences, and Solutions (pp. 274–298). New York University Press.

Wertheimer, M. (1912). Experimentelle Studien über das Sehen von Bewegung. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 61, 161–265.

Wertheimer, M. (1923). Laws of organization in perceptual forms. Psychological Research, 4, 301–350.

Zeigarnik, B. (1927). Über das Behalten von erledigten und unerledigten Handlungen. Psychologische Forschung, 9, 1–85.