Being Conrad!

The Role of Proximity in Friendship Development

At my first job in public health, our team decided to implement a social network analysis of our staff. The goal was to better understand this research methodology and gain the added benefit of understanding our level of connectivity through visualizations of our web of relationships across our slice of the organization actually functioned. When the results came in, the office buzzed with curiosity. The visual map displayed each of us as a node, linked by lines representing our interactions. As we gathered around the chart, people quickly tried to find themselves, tracing their connections and comparing the results with their expectations.

AI Cartoon of Social Network

The biggest surprise? The central hub, the person holding the network together, wasn’t a supervisor, a department lead, or someone from HR. It was Conrad, the guy who handled the informal coffee fund for our wing of the office. At first, this seemed funny. Conrad, the caffeine coordinator, was apparently the heart of our network. But when we thought about it, it made perfect sense. Conrad was a natural resource connector. If your SAS code was giving you trouble, Conrad could help you debug it. If you needed to know which study teams were working on similar topics, Conrad had the inside scoop. Having been at the organization for years, he knew who had expertise in what and could point you toward colleagues who could help you find synergies or share tools. Most importantly, Conrad was approachable, kind, and easy to talk to. Without an official title or any formal authority, he had built a network of relationships that made him indispensable.

Conrad’s role is a perfect example of how proximity influences friendship and connection. I realize that the “Conrad” at some offices isn’t as awesome as our Conrad. Yet, research suggests that the people we grow closest to are often those we encounter repeatedly, in spaces where familiarity builds and trust grows. Proximity plays a profound role in shaping who we connect with and how these relationships develop over time. For men, who often report having fewer close friendships as they age, understanding how proximity works can help them nurture deeper, healthier connections.

The Science of Proximity and Familiarity

Understanding proximity starts early in life and continues to influence our relationships throughout adulthood. This section moves from the impact of closeness during childhood and adolescence, to how repeated exposure builds comfort, and finally to how structured spaces can support deeper connection, especially for men.

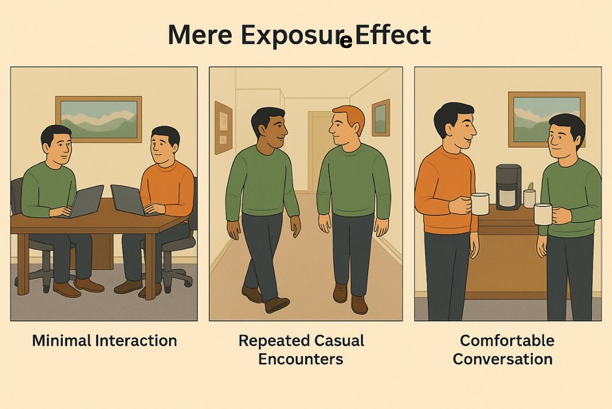

AI image of the mere exposure effect. It would not spell exposure correctly…

During adolescence, physical proximity plays a particularly powerful role. Studies of school children show that even something as simple as being seated next to someone increases the chances of becoming friends (Rohrer et al., 2021; Preciado et al., 2012). Research shows that when young people are exposed to peers with different life experiences in close physical spaces, they are more likely to form diverse friendships (Gitmez & Zárate, 2022). These connections can have lasting impacts on empathy, leadership skills, and openness to new experiences.

One of the most important forces behind friendship formation is the mere exposure effect. This is the tendency to develop a preference for people and things we encounter often (Batool & Malik, 2018). Repeated, simple interactions like passing someone in the hall or chatting briefly before a meeting can build comfort over time. Neuroscience supports this: brain imaging shows that being physically close to trusted friends activates regions associated with emotional safety and regulation (Morawetz et al., 2022). Just being near supportive people helps calm the brain and reinforces bonds.

Men benefit from structured opportunities to practice self-disclosure in safe environments (McKenzie et al., 2018; Snyman, 2025). For example, men’s groups, faith-based meetings, or therapy spaces can help build skills that translate into deeper personal friendships. Structured settings can counteract traditional masculine norms and create safe relational contexts for men to share information beyond sports, cars, technology, and work. This gradual process is essential for cultivating strong, emotionally supportive friendships.

In workplaces and other structured environments, proximity affects relationships in different ways based on people's positions or roles. Workers tend to choose friends based on who is nearby, while managers may form friendships based rank or strategic value. For men, shared spaces like break rooms or gyms can help form connections across these divides, though barriers of power or prestige may still limit openness (Schutte & Light, 1978). Interestingly, studies have found that proximity can sometimes override hierarchical boundaries when individuals interact frequently in informal settings. This highlights the potential of intentional workplace design to foster better relationships and improve organizational culture.

Proximity sets the stage for connection, but it’s what happens within that closeness, including the conversations, shared experiences, and willingness to open up that determines the quality of a friendship. Familiarity reduces uncertainty, making it easier for people to take social risks and show authenticity. This process is particularly important for men, who are often socialized to work independently and appear as though they have total control of their work and emotions (Shattuck et al., 2024). When men repeatedly encounter each other in safe, familiar settings, it creates opportunities for meaningful interactions to unfold gradually.

Gendered Patterns in Friendship

Men and women tend to form and maintain friendships differently. Women often have larger, more emotionally expressive networks that include family and confidants. Men’s networks are typically smaller and activity-based, which makes regular proximity even more crucial. Men also tend to spend time in predictable, narrow ranges of spaces with same-gender peers, while women’s social interactions are spread across more diverse settings (Yang et al., 2016; Dunbar et al., 2024).

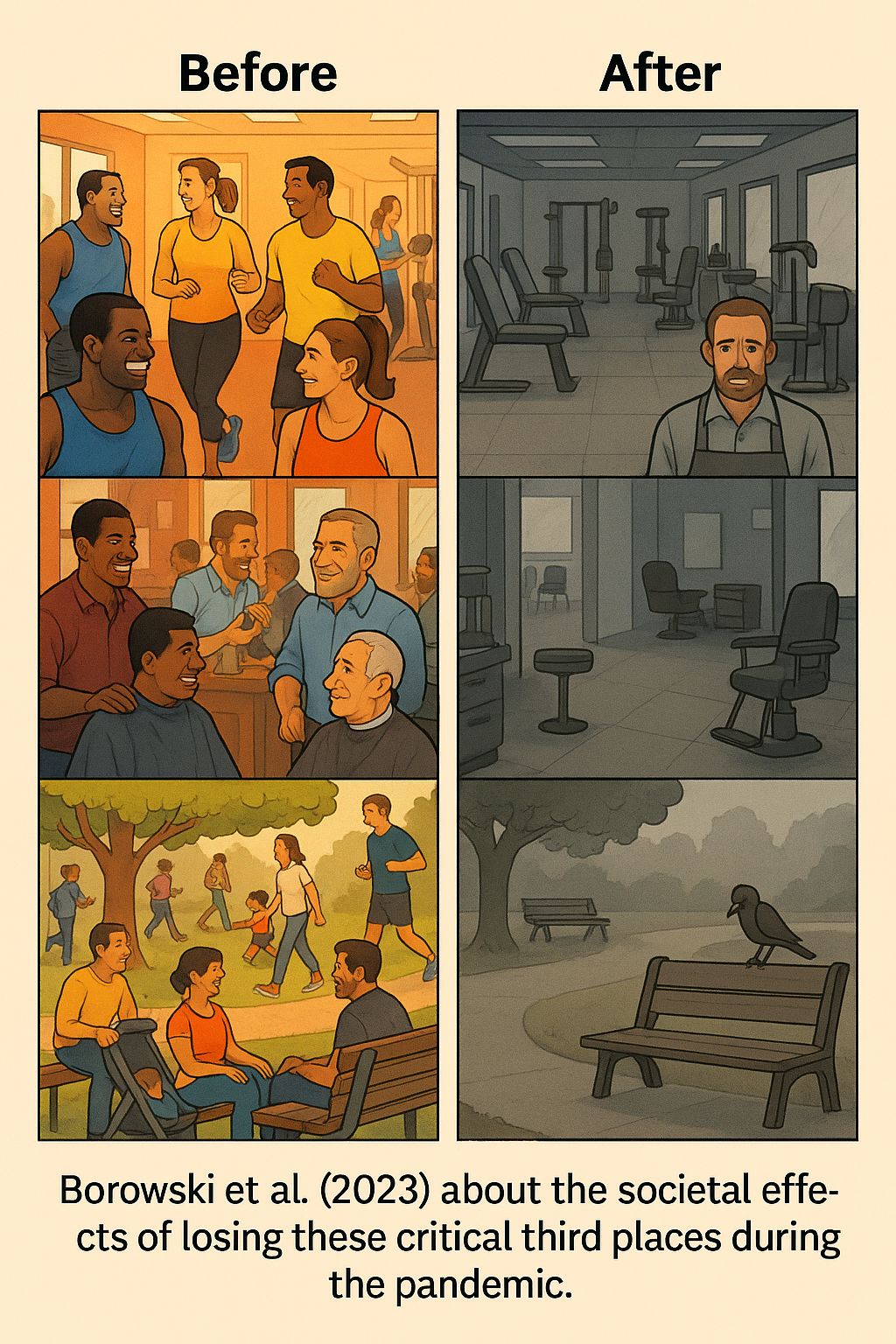

These sites of engagement are referred to as “third places”—informal public spaces like cafes, gyms, or parks where people gather, socialize, and build community outside of home and work. Without gym sessions, weekly poker games, or after-work meetups, men’s connections are likely to weaken. The COVID-19 pandemic allowed researchers to measure the impact of losing these third places on both physical activity and interpersonal engagement. Studies like Borowski et al. (2023) support the assumption that when these communal spaces closed, society experienced a measurable decline in social connection and well-being.

The loss of third places was popularized in Robert Putnam’s book Bowling Alone, which argued that as convening spaces and activities like bowling leagues diminished, Americans became increasingly disconnected, undermining social capital and community vibrancy. Putnam’s book and the pandemic both demonstrated the harm caused by losing those third places. Albrecht et al. (2022) show that spaces can be intentionally designed to facilitate social engagement, such as office common areas, community centers, parks, coffee shops, and retail areas. These thoughtfully designed spaces create opportunities for connection and trust-building.

Practical Strategies for Building Friendship Through Proximity

Create rituals: If possible, meet friends in the same place weekly, like a coffee shop or basketball court. Even if everyone can't make it every week, having time set aside is important. Rituals provide predictability and consistency.

Build micro-moments: Small, repeated interactions, even a quick greeting (honking when driving by someone's house or a quick text to let them know you're thinking of them) strengthen connections over time.

Vary your spaces: Explore new places together. A new hike, bike route, restaurant, or even switching up the dip during a football game - so long as it doesn't jinx your team! Shared exploration builds shared memories.

Open up gradually: Not everyone is ready to receive heavy conversations. Start with surface-level sharing, then deepen conversations at a comfortable pace. Even if the other person doesn't say anything, acknowledge your appreciation of their listening.

Use technology wisely: Texts, group chats, and video calls can maintain closeness, but occasional in-person time is key. Be less annoying about it than I am. I tend to think everything is funny and not all the other guys do. :)

Step outside your group: Seek friendships beyond your usual circle to increase diversity and understanding. It's good to mix up your engagement so that you can appreciate the richness of your friend group.

Create community hubs: Support parks, libraries, and recreation centers that naturally bring people together. Consider volunteering together. This is a great way to engage others and invest in your immediate and wider community.

Conclusion: Showing Up Matters

Conrad, the coffee fund coordinator from the opening story, wasn’t a manager or leader on the organizational chart. His power came from his consistent presence and helpfulness. Friendship isn’t only about shared values or deep conversations. It begins with showing up, physically and emotionally. By being intentional about proximity, men can create and sustain meaningful connections that enrich their lives and communities.

References

Albrecht, T., et al. (2022). Creating spaces for community engagement and health improvement.

Batool, S., & Malik, N. (2018). Role of Attitude Similarity and Proximity in Interpersonal Attraction among Friends.

Borowski, A., et al. (2023). The impact of third place closures on social connection and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dunbar, R.I.M., et al. (2024). Sex differences in close friendships and social style.

Gitmez, A. A., & Zárate, R. A. (2022). Proximity, Similarity, and Friendship Formation: Theory and Evidence.

McKenzie, S. K., Collings, S., Jenkin, G., & River, J. (2018). Masculinity, social connectedness, and mental health: Men’s diverse patterns of practice. American Journal of Men's Health, 12(5), 1247-1261.

Morawetz, C., et al. (2022). Friends and emotional regulation related brain activity.

Preciado, P., et al. (2012). Does proximity matter? Distance dependence of adolescent friendships.

Rohrer, J., Keller, T., & Elwert, F. (2021). Proximity can induce diverse friendships.

Rubin, Z., & Shenker, S. (1978). Friendship, proximity, and self-disclosure.

Schutte, J.G., & Light, J.M. (1978). The Relative Importance of Proximity and Status for Friendship Choices in Social Hierarchies.

Shattuck, D., et al. (2024). Building Bridges: A review of men's health and friendship interventions.

Snyman, R. (2025). Barriers to and facilitators of self-disclosure by male victims of childhood abuse. Children and Youth Services Review, 125, 105123.

Yang, Y., et al. (2016). Gender Differences in Communication Behaviors, Spatial Proximity Patterns, and Mobility Habits.