Personal Fouls and Personal Growth

What If NFL Players Had to Say, “I’m Sorry”?

Last night, I watched a defensive player arrive a heartbeat late on a throwing quarterback and their helmets collided. The hit wasn’t vicious, and appeared unintentional, but it was helmet-to-helmet contact. A flag flew, the stadium swelled with boos, and the defender walked away with the familiar head-tilt that says some mix of annoyance and calculation: worth it? As he paced, the refs discussed the foul and the quarterback threw his hands up to make the case. I caught myself wondering: what would happen if, before the next snap, the defender had to jog over and say “I’m sorry,” preferably not a sarcastic apology, not for the cameras, just a short acknowledgment of harm or not following the rules? Maybe throw in a fist bump.

Would it de-escalate the moment or deflate the game? Would it model respect or feel like a hollow ritual? And what might the science of apologies tell us about making that tiny exchange matter?

What counts as a “Personal Foul” in the NFL?

In the NFL, personal fouls are the category of on-field actions that endanger opponents or violate sportsmanship: unnecessary roughness, late hits, hits on a defenseless player, facemasks, horse-collars, illegal low blocks, and a range of unsportsmanlike behaviors. The standard enforcement is 15 yards, and on defensive personal fouls the offense is awarded an automatic first down. Flagrant or repeated violations can draw disqualification (ejection) and later fines or suspensions.

So personal fouls sit at the intersection of safety, respect, and competitive aggression. That’s exactly where an apology would have to work, right?

“Horse collar” tackle in an NFL game.

What is a “Good” Apology, Scientifically?

Apologies aren’t all created equal. Decades of research outline the ingredients that make them land. One influential line of work shows that the more components an apology includes, the more effective it tends to be, especially acknowledgment of responsibility and an offer to repair (Lewicki, Polin, & Lount, 2016). In two studies, researchers identified six common components and found that some matter more than others: taking responsibility and explaining what happened.

Aaron Lazare’s classic framework similarly emphasizes four functions: acknowledge the offense, explain (without excuse), express remorse, and make amends (Lazare, 2004). These are not academic niceties; they are the parts that help rebuild trust after harm.

Facemask penalty in the NFL

Recent syntheses go further. A meta-analysis of 175 studies found that apologies are among the strongest predictors of interpersonal forgiveness, but quality matters: sincerity, responsibility, and repair signals drive the effect (Yamamoto et al., 2021).

Other research describes why some transgressors struggle to deliver high-quality apologies, which include: threat to self-image, low perceived effectiveness, and low concern for the victim. Those factors can strip apologies down to empty phrases. If we can reduce those threats, we can nudge people toward fuller apologies (Schumann, 2014; Schumann, 2018). That isn’t easy.

Fight during an NFL game.

But What About Forced Apologies?

Here the evidence is clear and cautionary.

Across legal, developmental, and social-psychological settings, voluntary apologies consistently outperform ordered or compelled ones on perceived sincerity and acceptance. In one review of court-ordered apologies, voluntariness predicted better victim reception; forced apologies were less accepted and seen as less sincere. Developmental research likewise suggests that compelled apologies, especially when remorse is absent can backfire, making recipients like the apologizer less.

Bottom line: if you make someone say “I’m sorry,” you raise the odds it rings hollow.

Would Requiring Apologies Help or Hurt the NFL?

We know where this is going, but let’s put the research into the particular ecology of an NFL game, where time is compressed, adrenaline spikes, and reputations harden fast.

Potential Benefits

De-escalation through acknowledgment

Even a minimal apology, a quick shoulder-pad tap and “my bad” could take the oxygen out of a tinderbox moment. Acknowledgment is the non-negotiable core of most frameworks, and it’s plausible that tiny signal helps both players reset.

Injury-safety norms.

When the league emphasizes safety, symbolic norms matter. If apologies became a visible post-foul ritual, they might reinforce a culture where “finish the play” coexists with “protect your opponent,” nudging borderline hits down a notch. This concept runs against the appeal of a violent sport that frequently links its players to gladiators. Remember, we’re playing along with the possibility that this could happen.

Role-modeling for fans and youth.

Millions of young athletes watch these moments. Seeing elite players acknowledge harm could normalize accountability without questioning toughness. This could be a win for sportsmanship that doesn’t require a sermon.

Brady & Manning post-game. Were they saying nice things, not nice things, or nothing and just getting the obligatory picture taken?

Potential Costs

Insincerity risk under compulsion

If the apology is required by rule, the data suggests that you risk turning a relational repair tool into a rote script. On the field, that could inflame rather than cool tensions—the “yeah, sure, sorry” that makes your blood boil.

Gamesmanship and performative contrition

Players might quickly learn to weaponize the ritual, apologizing to curry referee favor or mock an opponent. Fans already spot flopping; they’ll spot fauxpologies. Over-apologizers also face a penalty in perception: frequency without change lowers character judgments. We know the NFL doesn’t need more of that.

Time and flow

The NFL protects rhythm. Adding a mandatory exchange after every personal foul could clutter an already officiation-heavy sequence of flags, conferences, re-spots, and announcements.

What Would “Good Enough” Look Like on an NFL Field?

A full Lewicki-style apology with six components is unrealistic between whistles. But a context-appropriate apology could be as small as:

Eye contact and a tap on the pads

“Late. My bad.”

Brief check that the opponent is okay

That sequence fits the evidence on acknowledgment and respect, contains a shred of cost (vulnerability in front of peers and cameras), and avoids the pitfalls of compelled speech. I believe we can spot this now and again on Sundays.

More facemasking penalties.

Would It Change Outcomes? Let’s Have Some Fun.

Pro sports are driven by metrics. I’d like to add a few ridiculous ones that may actually be useful in our everyday lives. So, if the NFL or an independent research group ever piloted a voluntary-apology protocol, here are a few playful outcome metrics I’d love to test:

Apology Completion Percentage (ACP)

Of personal fouls assessed, how many are followed by a visible acknowledgment within 20 seconds? Does ACP correlate with fewer post-play scrums that draw offsetting flags? What is the association between ACP and flagged offenses later in the game and season?

Heat Decay Half-Life

Time from flag to the next potential confrontation. Does visible acknowledgment shorten the “resentment window”? Could a similar metric describe our own tempers, how long before we cool off after being cut off in traffic or getting a rude email?

Youth Spillover Index

In partnered high school leagues, track taunting penalties and unsportsmanlike conduct before and after a “pro-apology” campaign that highlights NFL examples. Likewise, imagine tracking how family conflict or workplace tension changes when people make it normal to say, “I could’ve handled that better.”

The “Nope” Check

Code instances where a player refuses to accept an apology and see whether those moments are predictive of later escalation—a test of whether acknowledgment helps even when forgiveness doesn’t follow. In everyday life, that’s the dinner-table equivalent of doubling down when someone offers a truce.

Ridiculous? Yes. But the serious point stands: the science says apologies can help when they are voluntary, sincere, and paired with changes in behavior. They help least, and sometimes hurt, when they are compelled and unaccompanied by reform. Thinking about how this would play out in the most widely accepted violent context of our culture is an exercise for our own lives, too. How might it look if we tried a similar approach while driving in traffic, being courteous at the grocery store, or during a tough call with a customer service representative? Offering a simple, genuine acknowledgment when we inconvenience or frustrate someone could shift our daily interactions from tense to humane. A quick nod, a wave of thanks, or a kind tone on the phone can lower the temperature and build small reserves of trust. The practice of sincere apology and quick repair whether on a field, behind a shopping cart, or behind a steering wheel reminds us that accountability is not weakness; it’s connection.

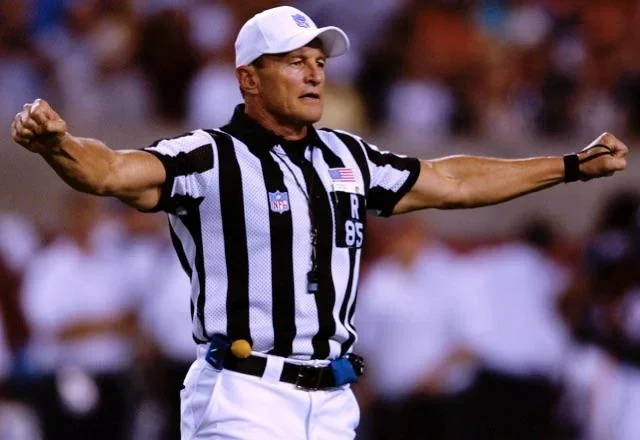

Maybe the retired “Ref with Guns”, Ed Hochuli could have persuaded apologies from some players? :)

Closing Thought

Apologies in our everyday lives are tiny opportunities to rebuild trust and invite grace. A brief “I’m sorry” offered in good faith can clear the air, restore a moment of shared respect, and remind us that we all foul up sometimes. Sure, this probably wouldn’t fly in the NFL, imagine Lawrence Taylor, James Harrison, or Aaron Donald pausing mid-field for a heartfelt apology, but in our ordinary lives it works wonders. When we take responsibility, we not only repair the small tears in our relationships but model for others that dignity and humility can coexist. The more often we practice those gestures, the easier it becomes to make them reflexive. Over time, those small moments of repair may be what keep our connections and communities intact.

References

Lewicki, R. J., Polin, B., & Lount Jr., R. B. (2016). An exploration of the structure of effective apologies. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 9(2), 177–196.

Lazare, A. (2004). On Apology. Oxford University Press.

Yamamoto, K., Matsui, H., & Ohtsubo, Y. (2021). Sorry, Not Sorry: Effects of Different Types of Apologies—A Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 693547.

Schumann, K. (2014). Why and when people avoid apologizing: The role of self-image threat and perceived effectiveness of apologies. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 55, 110–117.

Schumann, K. (2018). An emerging perspective on the psychology of apologies. Current Opinion in Psychology, 26, 91–95.